Chapter 1 Adapting to climate change: Our long-term strategy

This plan was published in 2022. Some actions in the plan were amended in January 2025 as part of the Government's response to the Climate Change Commission's national adaptation plan progress report. These updates reflect changes in circumstances since the plan was published and align with the Government’s climate strategy.

See the response and updated table of actions for more details.

This chapter sets out the current and projected impacts of climate change on Aotearoa and the long-term adaptation strategy that will help New Zealanders prepare for and adapt to these impacts.

This chapter outlines:

We must adapt to the impacts of climate change.

In the past 100 years, our climate has warmed by 1.1°C. Aotearoa New Zealand is experiencing more hot days and fewer cold days – 2021 was the warmest year on record, surpassing the previous record set in 2016.* Higher temperatures change our physical environment and weather patterns, presenting new and greater risks to the wellbeing of people and communities and their ways of life, buildings and infrastructure, our natural environment and the economy. Sea-level rise is accelerating, with an average rate of rise of 3.7 millimetres per year between 2006 and 2018.** By 2100, median sea-level rise in Aotearoa is projected to increase by a further 0.44 metres on average under a low-emissions scenario and 0.83 metres on average under a high-emissions scenario. Under the highest emission scenario, sea-level rise in Aotearoa is projected to increase by 1.09 metres on average.***

This poses a complex adaptation challenge. We must adapt to both slow-onset changes (such as rising sea levels that threaten coastal ecosystems and infrastructure) and increased frequency and magnitude of extreme events – such as coastal inundation and flooding that can damage homes, roads and other infrastructure, and affect access to coastal areas.

* See the Aotearoa New Zealand Climate Summary: 2021 from NIWA [PDF, 1.8 MB]

*** See the Interim guidance on the use of new sea-level rise projections.

Extreme weather events – such as storms, heatwaves and heavy rainfall – are likely to be more frequent and intense.* Tropical cyclones are likely to have increased wind intensity and rain rates, and to be stronger and cause more damage. More frequent and intense rainfall could reduce the availability of safe drinking water if treatment systems get overwhelmed, creating a significant risk to public health.

Projections show there will be fewer frost and snow days. Changes to the number of snow days will have significant impacts on hydrology and the seasonal cycle of snowmelt. This will affect the biodiversity of ecosystems, the energy sector and irrigation. Impacts will likely affect skiing and other snow activities, and therefore the tourism industry.

Changes in temperature and seasonality will affect agriculture and horticulture – for example, where certain crops, such as kiwifruit, can be grown. It will also change the timing of key events in the natural environment, from when plants flower to when animals migrate.

We can expect more frequent and severe droughts, particularly east of the Southern Alps / Kā Tiritiri o te Moana. That will put pressure on our freshwater resources – potentially affecting the reliable supply of drinking water, electricity generation and recreational activities like swimming and fishing. The agriculture sector will also be vulnerable to declining crop yields and pasture growth.

Projections indicate we will have stronger, northeasterly airflows in summer and stronger westerlies in winter – particularly in the south of the South Island. This will also affect rainfall patterns. Projected changes vary substantially around the country and by season. Annual increases in rainfall are projected for the west and south of Aotearoa; annual decreases are projected for the north and east.

Higher temperatures and wind speeds, and lower rainfall and relative humidity are likely to raise the risk of wildfire.**, ***

* See the Climate Change Projections for New Zealand: Atmosphere Projections Based on Simulations from the IPCC Fifth Assessment, 2nd Edition [PDF, 8.1 MB]

** See the Improved Estimates of the Effect of Climate Change on NZ Fire Danger [PDF, 1.2 MB]

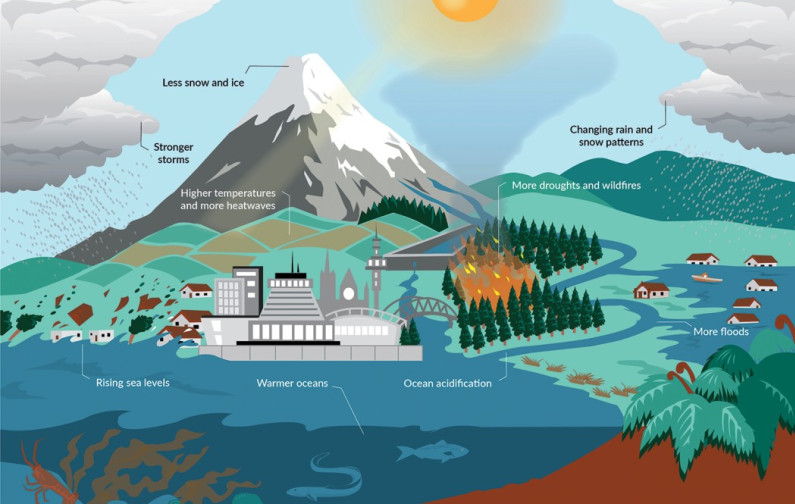

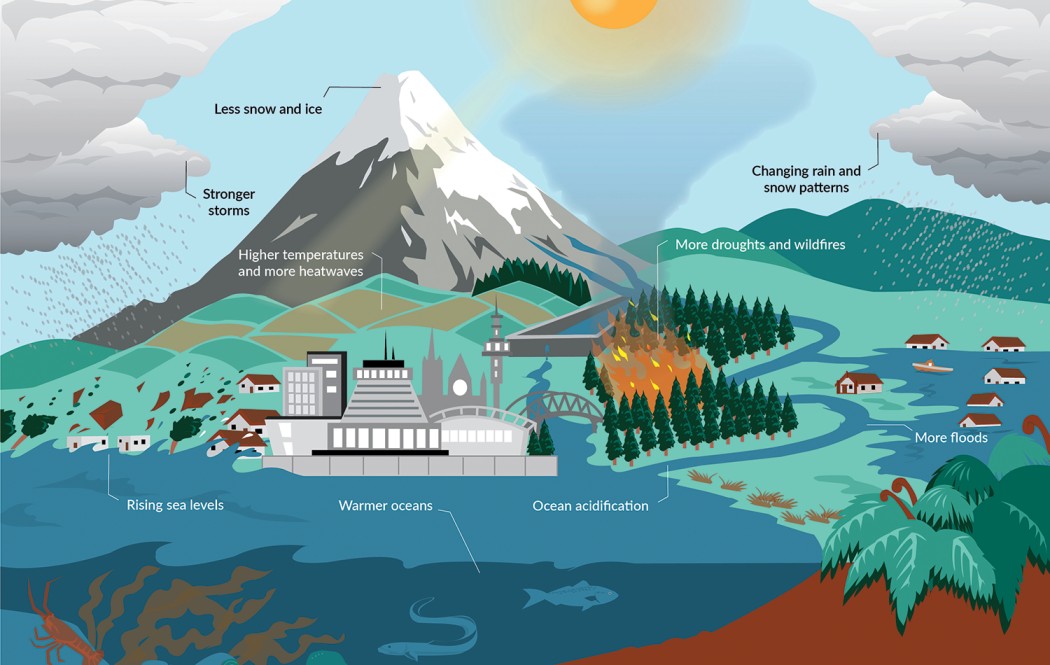

Figure 2 illustrates the range of changes projected as a result of climate change.

Eight impacts of climate change are listed: less snow and ice, changing rain and snow patterns, more droughts and wildfires, stronger storms, higher temperatures and heatwaves, rising sea levels, warmer oceans, and ocean acidification.

Eight impacts of climate change are listed: less snow and ice, changing rain and snow patterns, more droughts and wildfires, stronger storms, higher temperatures and heatwaves, rising sea levels, warmer oceans, and ocean acidification.

The scope of these projected changes is broad. Some will increase the intensity and frequency of natural hazards that have large-scale social and financial costs. We will need to ensure our communities, homes, buildings and places are resilient enough to cope with these. Other impacts will arise from general changes in weather patterns. For example, older people may suffer heat stress from a warmer climate, farmers may need to cope with drier conditions, and warmer oceans will affect our aquaculture industry.

We therefore need to use a diverse range of climate change scenarios that cover a number of possible futures. This allows us to prudently plan for a range of outcomes, including testing worst case scenarios. A degree of uncertainty is not a reason for inaction. Limiting the level of climate warming by mitigating emissions and building resilience to climate risk is the most effective way to reduce further losses and damages from climate change.

Our adaptation journey will also bring new opportunities along the way.

Warmer climates and the process of adaptation could bring lower winter heating costs, increased agriculture and horticulture productivity in new places, new fisheries species, more business and employment opportunities in sustainable sectors and new tourism offerings.

Actions in chapter 10: Economy and financial system, such as action 10.3: Deliver the Aquaculture Strategy, action 10.7: Continue delivering the Sustainable Food and Fibre Futures Fund and action 10.8: Establish innovation grants, can help New Zealanders harness upsides from the transition.

Seizing those opportunities will help us adapt and build resilience in a fair, just and equitable way.

We are used to managing natural hazards in Aotearoa, but adapting to climate change requires a different approach.

Natural hazard management has tended to be static and reactive, taking past events as a proxy for their future likelihood and consequences. Climate change is exacerbating the natural hazards we typically experience – making them more frequent and severe. It is also changing weather patterns in ways that are not necessarily hazardous, but are still challenging.

We need to be proactive in building resilience to natural hazards and other climate impacts, and shape our responses in a holistic way. Climate-related risk over longer timeframes is inherently uncertain. We must be flexible, so we can change direction as new information and understanding comes to light.

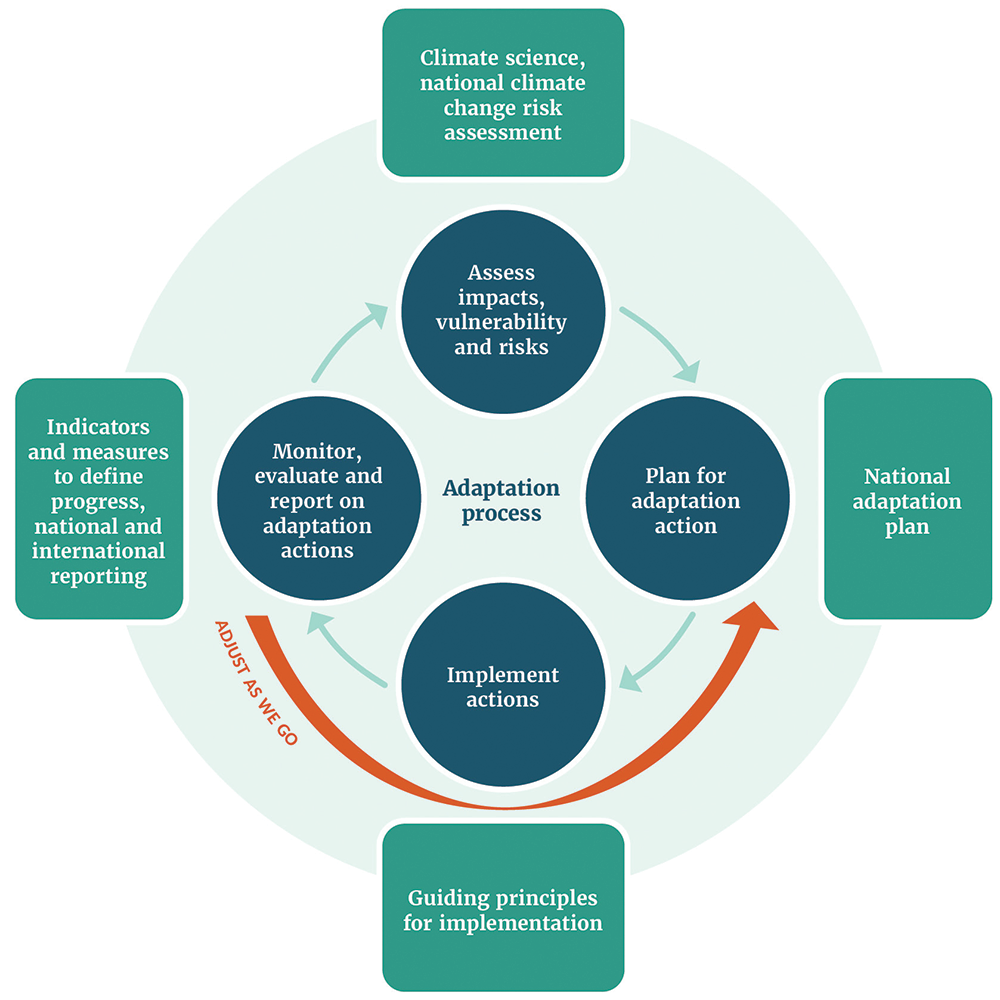

Adaptation is a process (see figure 3). It is a continuous journey of making a plan to assess risks, implementing the plan, monitoring and evaluating how effective the plan is, and adjusting as necessary.

The Climate Change Response Act 2002 establishes a process for that journey.

The Act requires the Climate Change Commission to prepare national climate change risk assessments every six years.* These will assess the risks to the economy, society, environment and ecology. They will also identify the most significant risks based on their nature, severity and the need for a coordinated response.

* The Government prepared the first national climate change risk assessment, but progress reports and subsequent risk assessments are to be prepared by He Pou a Rangi – Climate Change Commission.

The next step is to prepare a national adaptation plan in response to the assessment and release a draft for consultation. Once New Zealanders have had their say on the draft plan, the plan is finalised and implemented.

The He Pou a Rangi – Climate Change Commission will then prepare two-yearly progress reports on how effective the plan is in reducing the risks. The Government must respond to the Commission’s report within six months.

At this point, we have the opportunity to adjust the national adaptation plan to ensure it meets the intended outcome. We also have obligations to report internationally on our progress.

‘Adaptation process’ sits in the centre of this diagram. Around it are four bubbles connected by arrows flowing in a clockwise direction.

The bubbles are: Assess impacts, vulnerability and risks; Plan for adaptation action; Implement actions; Monitor, evaluate and report on adaptation actions. An additional arrow leads from this last bubble back to the Plan for adaptation action bubble. It is labelled ‘Adjust as we go’.

There are four boxes on the outer layer: Climate science, National Climate Change Risk Assessment; National adaptation plan; Guiding principles for implementation; and Indicators and measures to define progress, national and international reporting.

‘Adaptation process’ sits in the centre of this diagram. Around it are four bubbles connected by arrows flowing in a clockwise direction.

The bubbles are: Assess impacts, vulnerability and risks; Plan for adaptation action; Implement actions; Monitor, evaluate and report on adaptation actions. An additional arrow leads from this last bubble back to the Plan for adaptation action bubble. It is labelled ‘Adjust as we go’.

There are four boxes on the outer layer: Climate science, National Climate Change Risk Assessment; National adaptation plan; Guiding principles for implementation; and Indicators and measures to define progress, national and international reporting.

Adaptation is a journey we will take together.

Changing the way we do things – so our people, natural environment, built places and systems are resilient and can adapt – is an enormous challenge. But we can meet it by working together now to understand the risks, and taking action to manage them.

New Zealanders know from our vast experience with natural hazards – such as flooding and earthquakes – that we all have to prepare for them. Climate change is no different, although the range of impacts is wider than an increase in hazard events. We will all feel the effects and we all have a role in building resilience.

Central government, local government, iwi, hapū, whānau, the private sector, the research and scientific community, and communities and individuals all have different but complementary roles in our risk management system (see appendix 3). Central government cannot bear all of the costs of adaptation. Risk and costs will need to be shared between asset or property owners, their insurance companies, their banks, local government and central government.

Aotearoa is a resilient and innovative country. We need to work together to understand and prepare for the changes that will affect us.

Central government will take a leadership role in partnership with local government. It can establish regulatory and institutional settings that support effective adaptation – including, for example, supporting the right development in the right place. It can facilitate the availability of information and data for good risk-informed decision-making, and set direction to support local government and communities in their planning. Central government can ensure climate policy is a whole-of-government approach, in which each department or agency plays a part.

Central government also manages the investment in and risks to its own assets and to infrastructure. These include schools, hospitals, police stations and prisons, as well as services such as conservation and biosecurity. It also cares for a significant amount of Aotearoa New Zealand’s cultural heritage.

Central government funds post-disaster relief through mechanisms like the Toka Tū Ake EQC and the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA). It also supports vulnerable individuals through the welfare system. Increased resilience across the country can help the Government manage those costs, as well as the costs of maintaining its own assets and infrastructure.

Local government is at the centre of risk management planning and response because most hazard events occur at the local or regional scale. Climate change is felt locally, so local government will maintain its central role in helping communities to understand and respond together. Many communities and sectors are already collaborating to plan for a changing climate. Councils have statutory responsibilities to avoid or mitigate natural hazards and to have regard to the effects of climate change when making certain decisions. They are also responsible for civil defence and emergency management, and improving community resilience through public education and local planning. Their functions and duties relating to natural hazards include:

Councils also own assets, including infrastructure and forests, that are at risk from climate impacts.

Investment by local government in improved resilience can reduce the costs of new and improved infrastructure, support communities to pay rates, and reduce the likelihood of high‑cost interventions such as managed retreat.

Many councils are already addressing the impacts, and proactively integrating climate risk into current and future planning.

Māori play a unique role in adaptation – as Tiriti partners, tangata whenua and kaitiaki.

Māori as tangata whenua (people of the land) and kaitiaki (guardians) of their ancestral and cultural landscape will be affected by climate change. Certain whānau, hapū and iwi will be disproportionately affected, as will Māori interests, values, practices and wellbeing.

In accordance with the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, the Government and Māori will need to make decisions together in a way that balances kāwanatanga (the Government’s right to govern) with rangatiratanga (the Māori right to make decisions for Māori). Mātauranga Māori (indigenous knowledge) and an indigenous worldview will provide a valuable lens for planning and considering solutions.

The platform for Māori climate action in the first national adaptation plan will be a key mechanism for empowering Māori to play a role in adaptation planning for Māori, by Māori.

Iwi across the country are also showing how we can adapt and thrive in a changing climate. In December 2021, South Taranaki iwi Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi published Ka Mate Kaainga Tahi, Ka Ora Kaainga Rua – The Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi Climate Change Strategy [PDF, 11.1 MB]. The strategy outlines how the iwi will work with others in the community to better adapt to the impacts of climate change and reduce emissions. Similarly, the Te Arawa Climate Change Working group is working to protect cultural infrastructure and communities through the Te Ara ki Kōpū: Te Arawa Climate Change Strategy [PDF, 6.9 MB].

The private sector will face adaptation challenges. Businesses will need to strengthen their resilience to climate risks, including risks to their assets. Investment in resilience can both reduce risks and create new opportunities. Direct investment in adaptation can strengthen the resilience of infrastructure, production systems and supply chains. Good risk management includes understanding and developing strategies to manage these risks. Businesses may also find economic opportunities from better managing their risks, such as benefiting from new technologies and markets.

Banks and insurers may be exposed through their mortgage portfolios and liabilities. They can encourage resilience-building actions through their advice to customers, by providing loans or build-back-better post-event payments, and by sending market signals via their lending and insurance policies.

The research and scientific community can also contribute to adaptation. Adaptation decisions at all levels must be based on the best available science. Producing that science and making it accessible to address climate risk – by reducing vulnerability, building adaptative capacity and increasing long-term resilience – is a cornerstone of advancing Aotearoa New Zealand’s adaptation action. The research strategy in chapter 11: Implementing the plan provides guidance on research to help us on our adaptation journey.

Climate change is increasingly affecting daily life – for example, rising costs due to disrupted supply chains, power cuts due to extreme weather, and the need to evacuate homes due to flooding or fires. Communities and individuals need to be involved in adaptation. Good information about the risks and impacts will help them make informed choices.

Individual asset owners will need to manage risks to their own assets – reducing risk, minimising the impacts of natural hazards when they occur, and avoiding adding to risk through poor development choices.

In many areas, the private sector is already taking action to manage risks from climate change. One example is the Climate Leaders Coalition (the Coalition).

The Coalition brings together more than 100 chief executives from various industries who have committed their organisations to taking voluntary action on climate change. The Coalition’s mission is to respond through collective, transparent and meaningful action. For 2022, one of the Coalition’s focus areas is adaptation. This means understanding the risks businesses will face and planning for these to help build resilience.

In 2021, close to a third of the signatories assessed and disclosed their risks, and more than half are working to disclose soon. Among the signatories, 80 per cent are already considering risks in their investments and planning. The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures framework is their preferred approach to assessing risks, and more than a third are either fully or partially compliant with it (as at April 2021).

By making the consideration and management of climate risk part of their operations, as well as reducing emissions, businesses are planning now for the future.

Upholding the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi is a central aspect of the Government’s long‑term adaptation strategy. That means the Government will develop adaptation responses in partnership with Māori – including elevating te ao Māori and mātauranga Māori in the adaptation process – and empower Māori in planning for Māori, by Māori. The platform for Māori climate action provided for in the first national adaptation plan will be central to establishing a foundation for this partnership.

Many Māori communities are located in rural and remote locations, and are particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change on their homes, infrastructure and sites of cultural significance to Māori – including marae, urupā (burial grounds), waahi tapu (sacred sites) and mahinga kai (food gathering sites). In the Tairāwhiti rainfall event in March 2022, Anaura Bay – a coastal community with a high Māori population – was cut off due to widespread flooding and road slips. Hinetamatea marae suffered significant damage and part of the urupā was washed out to sea. Similar stories of other remote communities – in Mohaka, Raupunga, Tolaga Bay, the Waikato, and the Wairua Lagoons – of road closures, power cuts, kaimoana contamination and the potential for further displacement were told in submissions and workshops during the consultation phase of this plan.

Mātauranga Māori at a hapū and iwi level will be critical to informing local and central government climate adaptation responses.

The Government will work together with Māori to support Māori to explore adaptation options for Māori, led by Māori as part of Action 3.3 Establish a platform for Māori climate action.

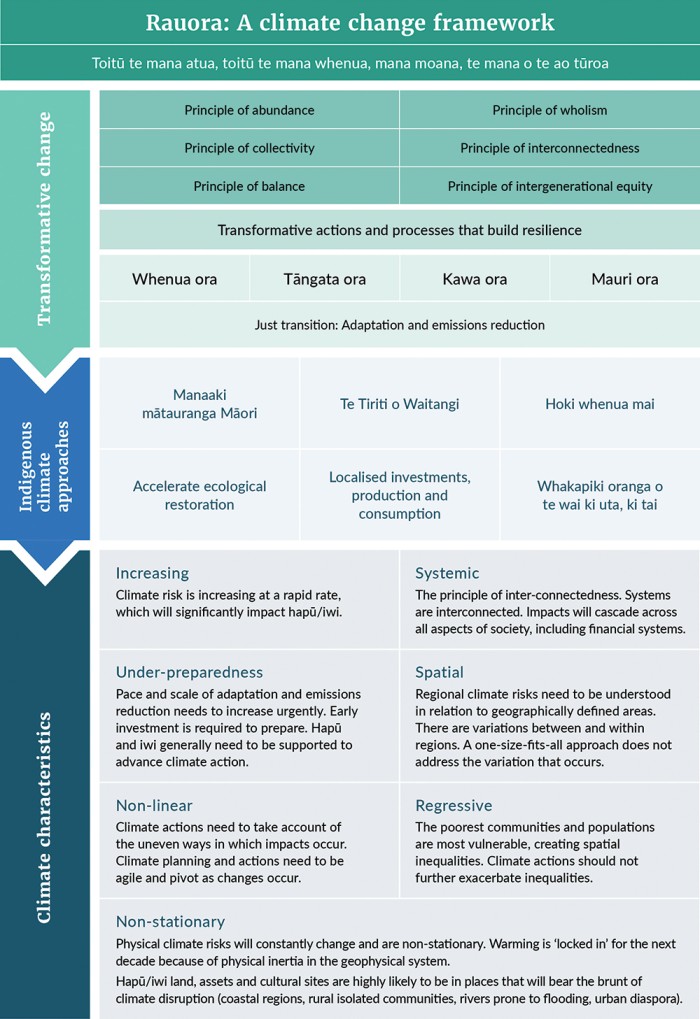

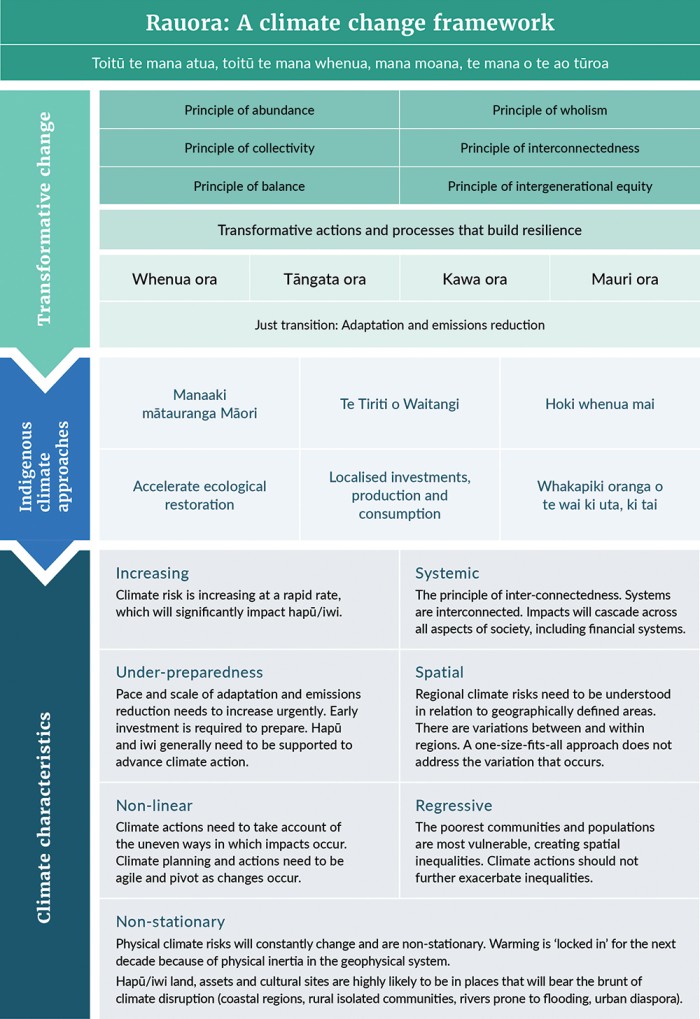

The Government recognises that its Tiriti partners have a worldview that sits outside western interpretations. It has commissioned Ihirangi to provide an indigenous worldview of the national adaptation plan – which is represented by the Rauora framework – to help facilitate its work in partnership with Māori.

The Rauora framework (figure 4) is published alongside this strategy and in chapter 2: Our first national adaptation plan 2022–28. It brings together Māori values and principles into an indigenous worldview of climate change. The Rauora framework is a lens through which the adaptation strategy and national adaptation plans will be progressed.

How the Rauora framework will inform our journey will be established in partnership with Māori through the platform for Māori climate action (action 3.3). The platform is a vehicle for both mitigation and adaptation action and is therefore also a key action in the emissions reduction plan. This is consistent with the Rauora principle of interconnectedness.

The Rauora framework is also a foundation from which iwi, hapū and whānau can apply their own mātauranga-a-iwi (knowledge with an iwi-specific base).

The notion of whenua ora, tangata ora, mauri ora recognises that the land, people and associated life forces are interconnected. In this way, a well land is a well people, and so too are the life forces of these components of the world healthy. The notion of kaitiakitanga is implicit in this approach, where Māori continue to strengthen their stewardship of the environment.

The Rauora framework supports and promotes transformative approaches, resilience building and supporting measures. It elevates and celebrates the contributions indigenous values and mātauranga Māori can bring to climate action.

Toitū te mana atua, toitū te mana whenua, mana moana, te mana o te ao tūroa.

Transformative actions and processes that build resilience

Just transition: Adaptation and emissions reduction

Increasing

Climate risk is increasing at a rapid rate, which will significantly impact hapū/iwi.

Systemic

The principle of inter-connectedness. Systems are interconnected. Impacts will cascade across all aspects of society, including financial systems.

Under-preparedness

Pace and scale of adaptation and emissions reduction needs to increase urgently. Early investment is required to prepare. Hapū and iwi generally need to be supported to advance climate action.

Spatial

Regional climate risks need to be understood in relation to geographically defined areas. There are variations between and within regions. A one-size-fits-all approach does not address the variation that occurs.

Non-linear

Climate actions need to take account of the uneven ways in which impacts occur. Climate planning and actions need to be agile and pivot as changes occur.

Regressive

The poorest communities and populations are most vulnerable, creating spatial inequalities. Climate actions should not further exacerbate inequalities.

Non-stationary

Physical climate risks will constantly change and are non-stationary. Warming is 'locked in' for the next decade because of physical inertia in the geophysical system.

Hapū/iwi land, assets and cultural sites are highly likely to be in places that will bear the brunt of climate disruption (coastal regions, rural isolated communities, rivers prone to flooding, urban diaspora).

Toitū te mana atua, toitū te mana whenua, mana moana, te mana o te ao tūroa.

Transformative actions and processes that build resilience

Just transition: Adaptation and emissions reduction

Increasing

Climate risk is increasing at a rapid rate, which will significantly impact hapū/iwi.

Systemic

The principle of inter-connectedness. Systems are interconnected. Impacts will cascade across all aspects of society, including financial systems.

Under-preparedness

Pace and scale of adaptation and emissions reduction needs to increase urgently. Early investment is required to prepare. Hapū and iwi generally need to be supported to advance climate action.

Spatial

Regional climate risks need to be understood in relation to geographically defined areas. There are variations between and within regions. A one-size-fits-all approach does not address the variation that occurs.

Non-linear

Climate actions need to take account of the uneven ways in which impacts occur. Climate planning and actions need to be agile and pivot as changes occur.

Regressive

The poorest communities and populations are most vulnerable, creating spatial inequalities. Climate actions should not further exacerbate inequalities.

Non-stationary

Physical climate risks will constantly change and are non-stationary. Warming is 'locked in' for the next decade because of physical inertia in the geophysical system.

Hapū/iwi land, assets and cultural sites are highly likely to be in places that will bear the brunt of climate disruption (coastal regions, rural isolated communities, rivers prone to flooding, urban diaspora).

Climate action for Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi, a small iwi in south Taranaki, is encapsulated in their recent climate change strategy [PDF, 11.1 MB]. The iwi and the Ministry for the Environment co-developed this as a case study in understanding the complexities of climate change for small post-settlement governance entities.

The strategy is entitled Ka Mate Kaainga Tahi, Ka Ora Kaainga Rua: When a place of abode retires, another as prepared emerges. This whakatauākī (proverb) refers to values from the iwi’s own ancestral pathways – preparedness, agility, resilience and future thinking – that ensure safety and survival.

Preparing a second place of abode sits in a broader context: extreme weather conditions and projected flooding patterns will affect marae, communities, hapū, culturally significant assets and businesses. Climate change is viewed as a phenomenon that will affect every facet of their lives. The strategy is more than an environmental plan; it includes social, economic, ecological and cultural implications.

“We have a responsibility to whanau, hapuu, marae and the iwi, to ensure that we are still here in 1,000 years’ time.” (Mike Neho, Tumu Whakarae, iwi chair, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi)

The strategy is informed by a Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi conceptual framework known as Te Kawa Ora, which promotes a balance between all things. The environment is viewed as an extension of iwi through whakapapa. To this end, relationships within the iwi and externally with others, including the environment, are viewed as fundamental to the approach. The strategy challenges the iwi to reharness their own tikanga (custom), kawa (protocol) and mātauranga-a-iwi (knowledge with an iwi-specific base) to advance climate action.

Developments include their papakāinga, partnerships in the energy sector, land purchases for new businesses, expanding alternative food sources and regenerating local flora and fauna.

Partnerships and alliances, capability and capacity building, and planning, implementation, research and evaluation are the cornerstones of this strategy. All are built on a foundation of Ngaa Raurutanga (the totality of customs, traditions, history and shared knowledge of members of the Ngaa Rauru iwi).

No two communities will experience climate change in the same way. Inequity arises through multiple domains, including income, housing, employment and accessibility. Climate change can also increase existing inequities. For example, some groups are more susceptible to harm due to where they live – such as coastal communities. Others may be disproportionately affected by financial impacts or lack the resources to adapt – such as low-income and beneficiary households – or have specific adaptation needs – such as older people and disabled people. Some regions are at risk from coastal erosion and flooding, while others are already dealing with drought. Tangata whenua face the loss of wāhi tapu (sacred sites) and taonga species.

Our adaptation strategy and national adaptation plans must support New Zealanders in ways that recognise their unique needs, values and circumstances.

Māori as tangata whenua are particularly sensitive to climate impacts on the natural environment for social, economic, cultural and spiritual reasons. Many Māori depend on primary industries for their livelihoods. In some places, climate change may alter patterns of use of mahinga kai (food-gathering sites) or rongoā crops (medicinal plants), and coastal impacts could disrupt access to marae or wāhi tapu.

Different groups experience extreme events and disaster responses differently. Older people may be more reluctant to evacuate their homes, because of income and accessibility and/or mobility issues, and may suffer from the loss of cultural and social networks. Ethnic minorities are more vulnerable in disaster responses due to language and integration barriers.

If communities need to shift, low-income groups have less choice about where to relocate and are less able to move elsewhere. Mobility-compromised and disabled people have specific needs that can be overlooked in the planning of new community locations and accessible housing.

Some groups feel the psychological and physical impacts of climate change more than others. Young people and children are more prone to psychological impacts from extreme events, while women are more vulnerable to domestic and sexual violence, which can increase in times of disaster. The mental health of members of farming and rural communities can be affected by the disruptions to livelihoods and loss of social cohesion.

Those with poorer health outcomes, such as Māori and Pacific people, children and older people, may also physically suffer more from increased heat and disease.

New Zealanders are already experiencing the impacts of climate change. As these impacts increase, there is a risk that existing vulnerabilities will deepen.

An equitable transition for all New Zealanders is important. To ensure that our transition is equitable, fair and inclusive, we will need to:

The Government has identified the following goals that underpin this long-term adaptation strategy:

These goals are consistent with the global goal on adaptation under the Paris Agreement and should be implemented in an interlinked and systemic way.

Aotearoa is also a signatory to several international agreements that support action to reduce vulnerability and enhance resilience. These include the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, as well as agreements under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) process, including the Paris Agreement.

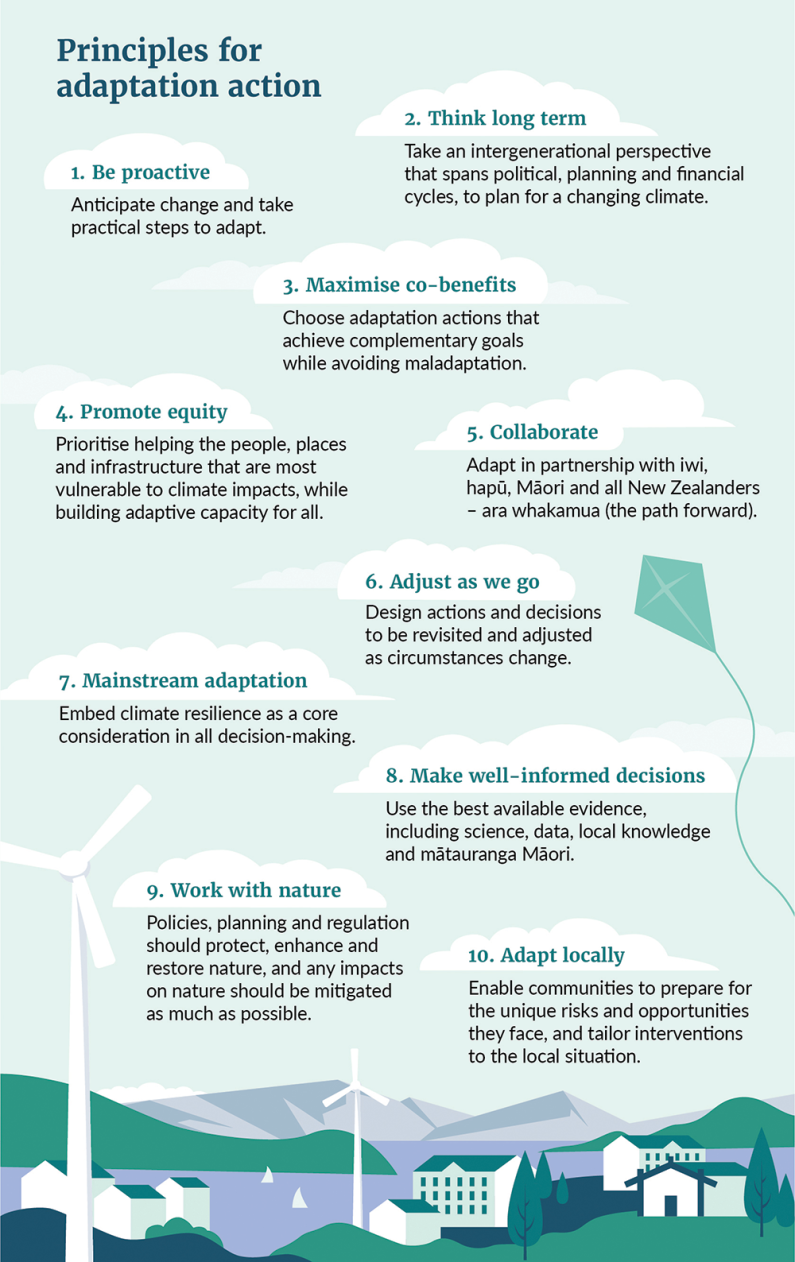

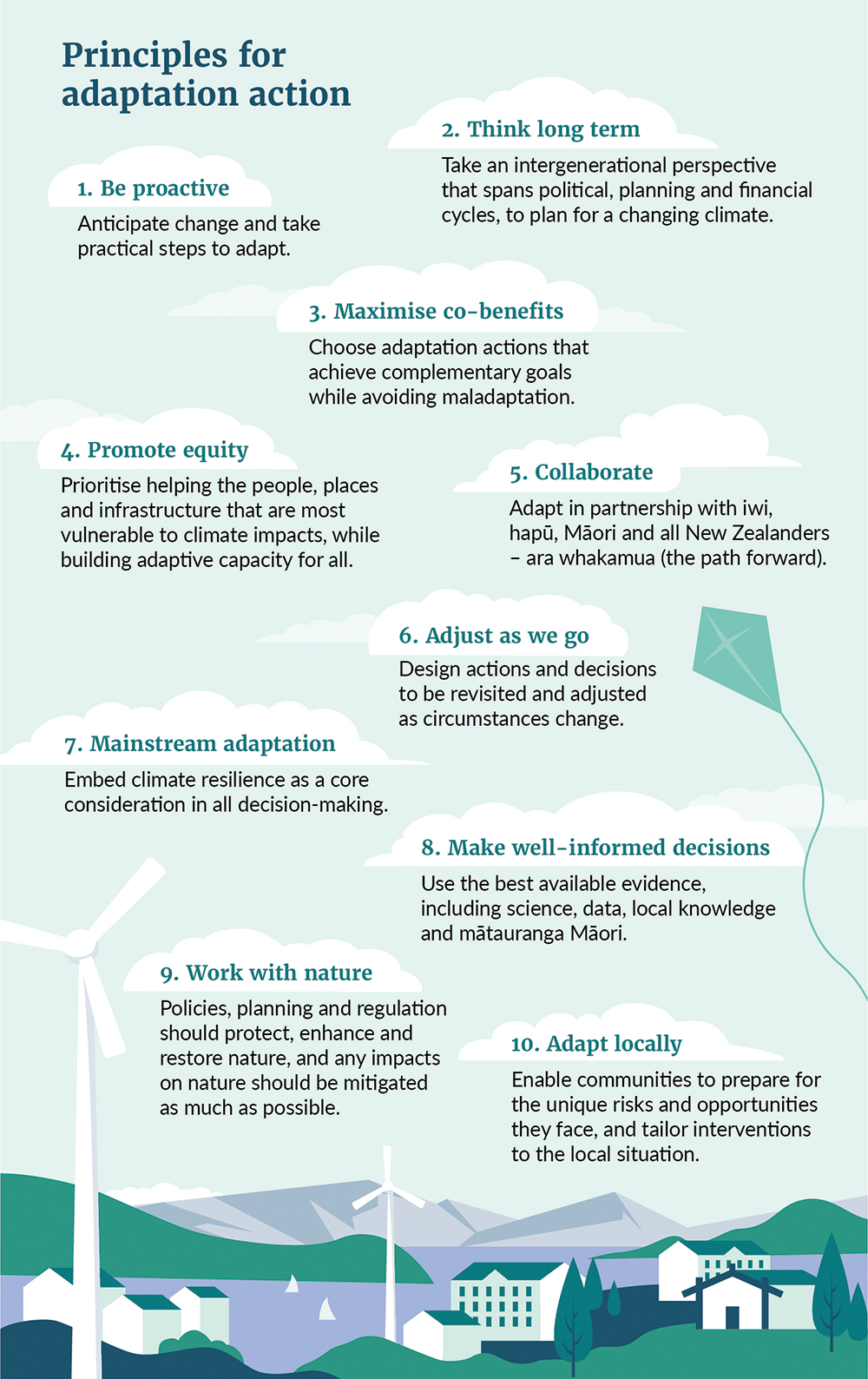

The Government has also identified ten principles that underpin the long-term adaptation strategy (figure 5). These principles reflect the need for our adaptation strategy to be intergenerational, flexible, proactive, responsive, holistic and inclusive – drawing on elements of the Rauora framework. These goals and principles underpin the priorities and adaptation actions in this first national adaptation plan. They will guide the implementation of this plan, and future national adaptation plans.

Anticipate change and take practical steps to adapt.

Take an intergenerational perspective that spans political, planning and financial cycles, to plan for a changing climate.

Choose adaptation actions that achieve complementary goals while avoiding maladaptation.

Prioritise helping the people, places and infrastructure that are most vulnerable to climate impacts, while building adaptive capacity for all.

Adapt in partnership with iwi, hapū, Māori and all New Zealanders - ara whakamua (the path forward).

Design actions and decisions to be revisited and adjusted as circumstances change.

Embed climate resilience as a core consideration in all decision-making.

Use the best available evidence, including science, data, local knowledge and mātauranga Māori.

Policies, planning and regulation should protect, enhance and restore nature, and any impacts on nature should mitigated as much as possible.

Enable communities to prepare for the unique risks and opportunities they face, and tailor interventions to the local situation.

Anticipate change and take practical steps to adapt.

Take an intergenerational perspective that spans political, planning and financial cycles, to plan for a changing climate.

Choose adaptation actions that achieve complementary goals while avoiding maladaptation.

Prioritise helping the people, places and infrastructure that are most vulnerable to climate impacts, while building adaptive capacity for all.

Adapt in partnership with iwi, hapū, Māori and all New Zealanders - ara whakamua (the path forward).

Design actions and decisions to be revisited and adjusted as circumstances change.

Embed climate resilience as a core consideration in all decision-making.

Use the best available evidence, including science, data, local knowledge and mātauranga Māori.

Policies, planning and regulation should protect, enhance and restore nature, and any impacts on nature should mitigated as much as possible.

Enable communities to prepare for the unique risks and opportunities they face, and tailor interventions to the local situation.

Chapter 1 Adapting to climate change: Our long-term strategy

August 2022

© Ministry for the Environment