Codifying the relationship between nature and people

Our Departmental Chief Science Advisor Dr Alison Collins and Senior Scientist Dr Anne Gaelle-Ausseil from Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research, as part of a fellowship with the Office of the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor, have been researching the relationship between wellbeing and nature. This is the summary of their work.

Our wellbeing is dependent on a healthy environment. Codifying this relationship helps us to appreciate and manage it better.

Our wellbeing is deeply dependent on our relationship with nature. Some of these relationships are visible and tangible; others we may not always understand, appreciate, or acknowledge.

Nature provides many benefits. Some of these are easy to see or put a monetary value on, such as the production of food, energy, or timber for building. Some benefits we know of but cannot see, such as nutrient filtration provided by wetlands, or pollination by bees. Then again, some benefits are personal and subjective, like appreciating the beauty of a pōhutukawa flower or relaxing beside Lake Taupō.

Many organisations are acknowledging the benefits nature provides. One example is a programme run in a partnership between the Department of Conservation and the Mental Health Foundation [Department of Conservation - Te Papa Atawhai]. During the COVID-19 pandemic the connection to nature emerged as a common way of coping with anxiety. Catherine Knight, in her book Nature and Wellbeing in Aotearoa New Zealand, reviews some of the growing body of evidence on the link between nature and mental and physical wellbeing. She notes that ‘even a short walk, an ocean view or a picnic by a river can leave us feeling invigorated and restored’ [The Conversation].

Wellbeing means giving people the capabilities to ‘live lives of purpose, balance and meaning’ [World Economic Forum]. New Zealand aroused international interest in 2019 when it took a wellbeing approach to governing and budget setting: ‘overall wellbeing and mental health, knowing how our environment is doing, these are the measures that will give us a true measure of our success’. A national Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy shortly followed, and since then many regional councils, schools, and workplaces have established wellbeing committees, charters, and strategies. Several organisations also evaluate performance against wellbeing frameworks (such as the Genuine Progress Index) [GPI].

Acknowledging this fundamental connection between nature and wellbeing is a step forward. However, to ensure the decisions we make do not have unintended consequences, either on nature or on our own wellbeing, it is important to build a more tangible and evidential understanding of this relationship. Some quantification or measure of the connection between nature and people is required to prioritise budgetary spending, formulate good decisions, and measure and evaluate impact and performance.

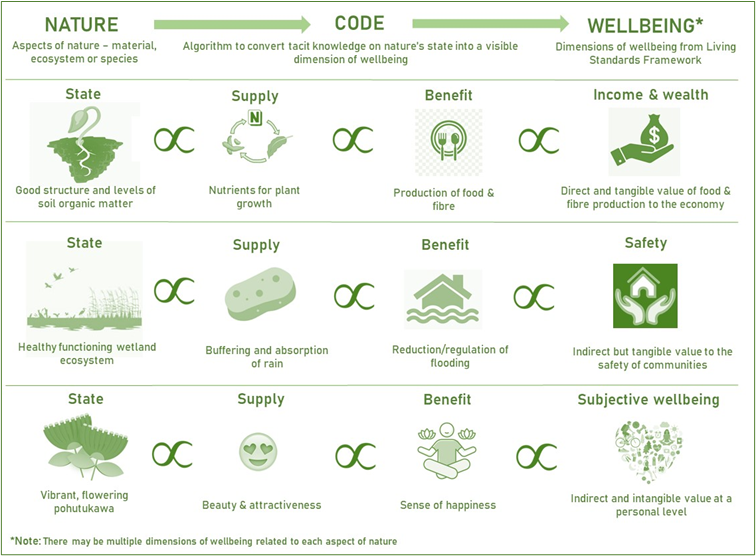

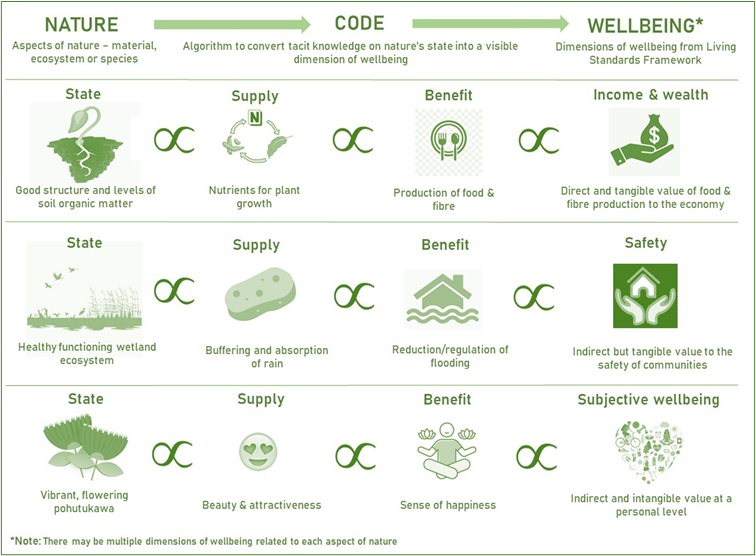

Codifying is a way to translate tacit understanding into an explicit, usable form. It can be a framework, an algorithm, or a set of rules to convert information into knowledge to support decision-making.

Several classifications and frameworks have been developed to help explore different parts of the relationship between nature and people. The Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), established in parallel to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), was formed to provide science-based information to policymakers on the risks of biodiversity loss to people’s quality of life. IPBES coined the term ‘nature's contributions to people’ (NCP) [ipbes], which it defined as ‘all the contributions, both positive and negative, of living nature (i.e., diversity of organisms, ecosystems, and their associated ecological and evolutionary processes) to the quality of life for people’.

The New Zealand Treasury has focused on codifying wellbeing in the form of a Living Standards Framework (LSF) [Te Tai Ōhanga - The Treasury]. Wellbeing is associated with four types of capital (social, built, human, and natural) and is defined by 12 domains (including health, housing, jobs, and earnings). Of all the links, however, the relationship between natural capital and wellbeing is the least developed.

To help combine the concepts of nature’s contribution to people (from IPBES) and wellbeing (as defined by the Living Standards Framework), we initiated a partnership between Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research, the Ministry for the Environment, and the Office of the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor. The project [Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research] proposes a process to codify the specific contributions of nature to specific aspects of wellbeing. The aim is to enable greater visibility of the full range of benefits provided by nature and recommend how we can monitor these contributions.

The result of this process represents the nature–people relationship in the form of a logic chain:

Nature is defined by a particular state.

↓

Supplies are materials, processes, and cognitive experiences that contribute to wellbeing.

↓

People receive benefits from these contributions.

↓

These benefits add to one or many dimensions of wellbeing.

For each contribution from nature, we can create a logic chain linking nature through state, supply, benefit and, ultimately, wellbeing, as illustrated more fully in the figure below.

Codifying connections between nature and wellbeing that are not always linear or logical is not straightforward. One of the most significant challenges we encounter is that people view their relationship with nature very differently, whether they value nature for nature’s sake, consider it as part of their culture, or see it as an external resource to fulfil their individual goals.

Depending on the perspective, values and benefits vary across individuals and communities, making it difficult to represent and conceptualise them. The concepts of nature’s contributions to people, and even more so ecosystem services, are in themselves people focused. They imply a one-way relationship, which may not resonate with being at one with nature, or principles of reciprocity, as is common in te ao Māori perspectives. This continues to be an important discussion in science, mātauranga and policy circles [Mandle et al. 2020 Nature Sustainability] [Pascual et al. 2021 Nature Sustainability] [Karacaoglu G 2021 The Tuwhiri Project] as well as in our own project.

A related challenge is that the relational and intrinsic values people place on nature are subjective, making it difficult to track and robustly monitor how a change in the environment affects individuals or groups. This also means that groups may have diverse opinions on the importance of nature for themselves or for their community, including the scale at which they experience, value and benefit from nature (for example, a flower, a river, a catchment, or a national forest of kauri trees).

While codifying the relationship between nature and people is difficult, it is a necessary step to ensure our decisions both acknowledge and protect nature and our wellbeing.

As noted by the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, by making the ‘invisible visible’ via codification, there is significant opportunity to improve the way we live, work, and govern. An appropriately informed wellbeing framework is more likely to ensure effective and equitable targeting of public spending, evidence-informed policies, and decisions that neither impact on, nor under-estimate, the contribution of a well-functioning environment to the economy, culture, and wider society.

The authors wish to thank their respective organisations for supporting their mahi, as well as Professor Ken Hughey and Dr Sam Carrick for their insightful review. Photographs are the authors’ own.

Codifying the relationship between nature and people

May 2021

© Ministry for the Environment