Chapter 1: Our climate, our future

Patterns of temperature, rain, wind, and sunshine make up the climate of Aotearoa New Zealand. Climate sculpts river valleys and mountains, influences which plants grow where, and defines our landscapes, making them instantly recognisable as New Zealand.

Image: UBCO

These patterns shape many ordinary facets of our lives too – the food on our plates, the sports we play, the crops we grow, and where we spend our leisure time and holidays. We know that warmer weather will bring fresh strawberries back to our plates. In some places we know to take an umbrella or a jacket when we go out – just in case.

Rain and sun also shape the climate of resourcefulness and ingenuity that defines the psyche of our nation. We are forced to be resilient, and take four seasons in one day in our stride. When extreme weather hits, it can build a feeling of community as people band together to clean up after nature has done her worst to our farms, roads, and houses.

Over time, we have learned to live and thrive with the climate of New Zealand. We tend to take our climate for granted because we generally know what to expect – even the unexpected.

In the beginning there was darkness. This time, te kore, was full of potential, and from it grew consciousness, an energy that grew and led into te pō, the time of the long night. As te pō went on, life began as the creation of two supreme atua (deities) – Ranginui the sky father and Papatūānuku the Earth mother.

Ranginui and Papatūānuku were bound together by their great love for each other. Many children were born and raised in the darkness between them. The children wanted to live and grow in daylight, so they debated whether to separate their parents. The separation took place and brought the children into the world of light, te ao mārama. The children of Ranginui and Papatūānuku are atua of the natural world.

One son, Tāwhirimātea, did not agree with the plan to separate his parents, but was unable to stop it. Tāwhirimātea is the atua of winds and weather and in his sadness and anger over his parents’ separation, he frequently attacks his siblings in the form of storms, cyclones, droughts, and extreme weather. Tāwhirimātea is the parent of kōhauhau (atmosphere) and āhuarangi (climate).

Another son, Tānemāhuta, is atua of forests, birds, and insects. It was Tāne who gathered the sacred red clay of Kurawaka to form the first human, and breathed life into her. She is known as Hineahuone. Tāne mated with Hineahuone and from her womb came the first human, Hinetītama (the dawn maiden), from whom all humans are descended.

This is one version of the Māori creation story that helps us understand our connection to the natural world, including the world’s climate and atmosphere. ‘Ko ahau te taiao ko te taiao ko ahau: I am the environment and the environment is me’ is a whakataukī (proverb) that articulates the Māori worldview that all the values and traditions that make us who we are, are gifts from Papatūānuku passed down through our ancestors. In turn, we must pass them on to those who come after us.

For Māori, the gifts are described as our taonga tuku iho (treasured gifts passed down through generations). They include mātauranga (knowledge), te reo Māori (the Māori language), manaakitanga (generosity), mahinga kai (food gathering), whanaungatanga (socialising), and kaitiakitanga (guardianship). They shape who we are as people and are deeply linked to our wellbeing and sense of identity.

Gathering harakeke for weaving with whānau (extended family), diving for pāua and kina with mates in the summer, and dropping off a sack of fresh kaimoana (seafood) to our kaumātua (elders) – these are the moments we live for. These practices also make us tangata whenua (people of the land). Our identity and sense of belonging depends totally on being able to have a balanced and reciprocal relationship with the environment.

But the things that matter most – our unique way of life, identity, and the values and traditions that make us who we are – are at risk of being altered or lost forever. The impacts of climate change are already being felt by vulnerable whānau throughout Aotearoa, and are causing pain and mamae (hurt).

Our responsibility as kaitiaki (guardians) of Aotearoa, is to protect and care for what we have been given, for future generations. Ours is only one moment in time. We can draw strength from carrying our ancestors with us in this challenge, ‘Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua: we walk backwards into the future with our eyes fixed on our past’. By working together, acknowledging the past and incorporating innovative and revolutionary ways of thinking, we can walk into the future with a greater understanding of how to accept the wero (challenge) that is climate change.

Greenhouse gases are accumulating in the atmosphere and changing the climate. These gases have mostly come from burning fossil fuels around the world for the past 200 years. Our daily activities – the transport we use and the products we make and buy – continue to be sources of emissions. Contributions to the build-up of greenhouse gases come from choices we make as individuals and as a nation, and from other countries.

As greenhouse gases accumulate in the atmosphere, they are altering climates around the world and in our own country. New Zealand’s average annual temperature has risen by 1.13 (± 0.27) degrees Celsius from 1909 to 2019. Sea levels are rising, and changes to drought and extreme rainfall are beginning to emerge.

Read the long description for Our changing climate

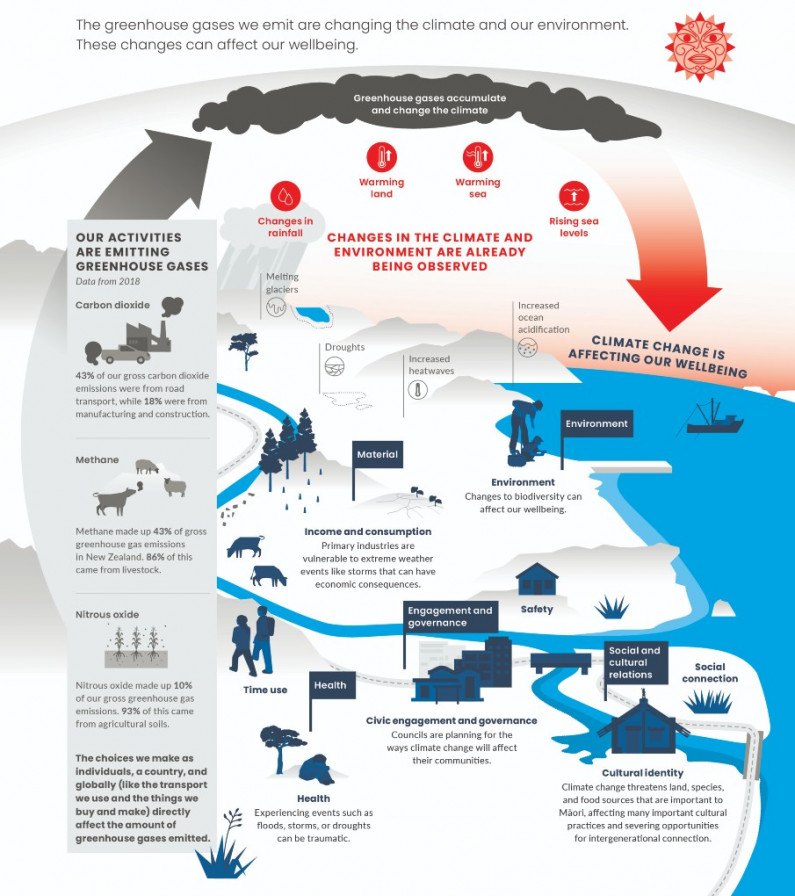

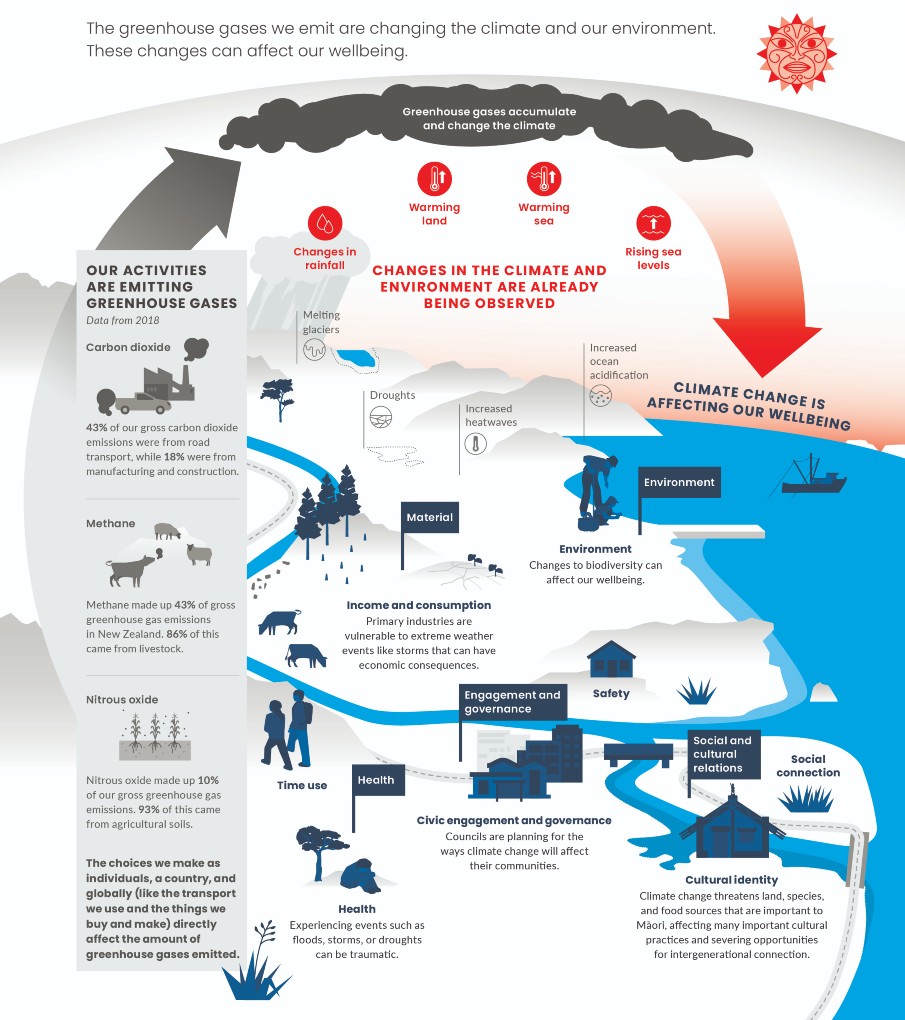

The greenhouse gases we emit are changing the climate and our environment. These changes can affect our wellbeing.

Our activities are emitting greenhouse gases (Data from 2018);

Carbon dioxide – 43% of our gross carbon dioxide emissions were from road transport, while 18% were from manufacturing and construction.

Methane – Methane made up 43% of gross greenhouse gas emissions in New Zealand. 86% of this came from livestock.

Nitrous oxide – Nitrous oxide made up 10% of our gross greenhouse gas emissions. 93% of this came from agricultural soils.

The choices we make as individuals, a country, and globally (like the transport we use and the things we buy and make) directly affect the amount of greenhouse gases emitted.

Greenhouse gases accumulate and change the climate. Changes in the climate and environment are already being observed;

Changes in rainfall, warming land, warming sea, rising sea levels, melting glaciers, droughts, increased heatwaves, increased ocean acidification.

Climate change is affecting our wellbeing;

There are five flags of wellbeing in this model – material, environment, health, engagement and governance and social and cultural relations.

Material – One consideration is income and consumption. Primary industries are vulnerable to extreme weather events like storms that can have economic consequences.

Environment – Changes to biodiversity can affect our wellbeing.

Health – Experiencing events such as floods, storms, or droughts can be traumatic.

Engagement and governance – Councils are planning for the ways climate change will affect their communities.

Social and cultural relations – Climate change threatens land, species and food sources that are important to Maori, affecting many important cultural practices and severing opportunities for intergenerational connection.

Emissions are changing the climate, and the changing climate is affecting us and our wellbeing. The native biodiversity of New Zealand and the places where we live, enjoy recreation, and make a living are also being affected. Some of the things we care about most – our ability to direct our own future, a secure life for our grandchildren, and our deep connections to the natural beauty of these islands – are all threatened by climate change.

Think about getting a coffee at your favourite café or shelling mussels at the marae with whānau (family). As changes in the climate build, coffee crops and other imports could be affected by disease, and the activities that bind generations together may have to change if kai can no longer be gathered in the same places.

When the climate we have built our lives and economy on begins to shift beyond natural variability, it creates unease and uncertainty. This can affect us as individuals, whānau, and communities, and our wellbeing suffers. The effects of a drought for example, can ripple through a region and affect the environment, the economy, and the mental health of the people who live and work there.

As a small, trade-reliant nation, New Zealand is highly dependent on connections with the rest of the world, and therefore on climate and behaviour elsewhere. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions globally would reduce the future impacts of climate change on us and the planet.

A small window of time remains to make these reductions to avoid the severe impacts of a world that is two degrees Celsius or more warmer. As a signatory of the 2015 Paris Agreement and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, New Zealand has committed to work with the rest of the world to limit future warming.

The global community has acted together before. When damage to the ozone layer in the stratosphere was discovered over Antarctica in the 1980s it was cause for global concern. This layer of ozone stops ultraviolet (UV) radiation reaching Earth’s surface, where too much can cause sunburn, skin damage, cataracts, and skin cancer. The Montreal Protocol was signed in 1987, and has resulted in the use of human-made chemicals that can destroy ozone being almost completely phased out.

The ozone hole has started to shrink. Current projections are that the Antarctic hole will gradually close and that ozone concentrations will return to mid-1980s levels in the 2060s (WMO, 2019). Without the protocol and the later amendments that further tightened actions on emissions, UV index values in New Zealand would now be 20 percent higher than those recorded in the early 1990s (McKenzie et al., 2019). (The UV index is a measure of the strength of UV radiation from the sun.)

There is growing public desire for New Zealand to do its part to secure a stable climate. Tens of thousands of New Zealanders marched and took part in climate strikes in 2019. They joined millions worldwide to show the high value of a stable climate for personal wellbeing and safety, the environment, and for future generations.

Throughout the country, regional councils and city councils have declared climate emergencies. Whānau, hapū, and iwi have been involved in discussions about how climate change is affecting their communities, and more companies than ever have committed to quantifying and understanding their emissions. In 2019, New Zealand passed the Zero Carbon Act to put emission reduction targets into law and start the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Burning coal, oil, and gas across the globe has fuelled the breakthroughs that have led to our modern life. New Zealand is fortunate to be rich in the clean resources – wind, geothermal, hydro-power, and solar – that will fuel our future. We have begun to embrace these sources of energy and in 2018, 84 percent of our electricity was generated from renewable sources (MBIE, 2019b).

In other parts of our lives we still depend heavily on activities that emit greenhouse gases. We love our cars, and in 2018 owned 0.8 cars and passenger vehicles per person – this was the highest rate in the OECD in 2017 (OECD, 2017). All those vehicles made up 27 percent of our gross carbon dioxide emissions in 2018 (only 10 in 1,000 light vehicles were hybrids and 2 in 1,000 were fully electric) (MoT, 2019). Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture made up close to half of our gross emissions in 2018. However, exports from natural resources or activity in primary industries (including agriculture) make up a large part of our export income (Stats NZ, 2019).

Our future is interconnected with the climate because climate shapes our social, cultural, and economic lives. But it is a two-way street – our actions and activities are also affecting the climate. This presents a responsibility and an opportunity for today. We have a responsibility to protect the people and places that will be most affected by climate change. This comes with an opportunity to play an active role in shaping our future so we are secure and resilient.

Climate describes the expected temperature, rain, or snowfall at a certain place on a particular day – like the average high temperature for August 15th at your local rugby field. An especially freezing afternoon or a heavy downpour during a game is the weather. These weather conditions are variations from the long-term average climate.

Our climate varies in response to human activities (like adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere) and to natural influences (like climate oscillations). Natural influences can cause the climate to fluctuate above and below a baseline, but by increasing the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, humans are changing the actual baseline.

Greenhouse gases (like carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide) in the atmosphere act like a blanket by retaining energy from the sun. They are vital for keeping the temperature on Earth in a range where life can flourish. For the past 3,000 years the average temperature in New Zealand has been relatively steady, rising and falling by less than a degree over this time (MfE, 1997).

Burning fossil fuels (like coal, oil, and gas), deforestation, and agriculture have increased the amounts of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and caused more energy to be trapped by Earth’s blanket. Most of the extra energy retained (more than 90 percent) has been absorbed by the oceans and raised sea temperatures and sea levels. Some energy is held in the atmosphere and makes our air and climate warmer (IPCC, 2014a).

Not all greenhouse gases have the same effect. Some, like carbon dioxide, are long-lived and can stay in the atmosphere for thousands of years. Long-lived gases build up when they are added to the atmosphere faster than they are taken out, effectively making the blanket thicker and thicker. Other gases, including methane, can be gone in years or decades but do a better job of holding heat in, and act more like a duvet than a blanket. These short-lived gases can have a significant warming effect if their levels are kept topped up by continued emissions.

Chapter 1: Our climate, our future

October 2020

© Ministry for the Environment