Pōhutukawa Loss, extinction, gratefulness to the environment (te taiao)

E tū Pōhutukawa e

Te kaikawe i ngā mate o te tau

Haere rā koutou ki te uma o ranginui

Haere ki te kete nui a tāne

Koia rā! Kua whetūrangitia koutou

Behold Pōhutukawa

Who carries the dead of the year

Onward the departed to the chest of the sky

Onward into the milky way

Indeed! You have become stars

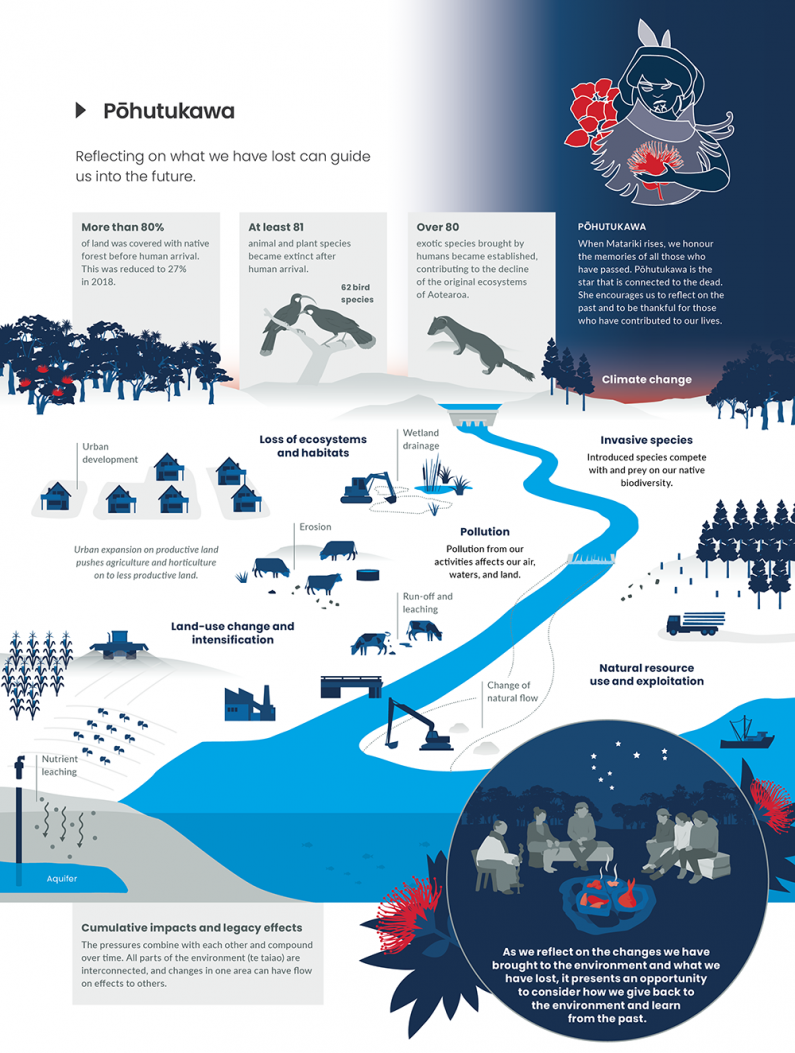

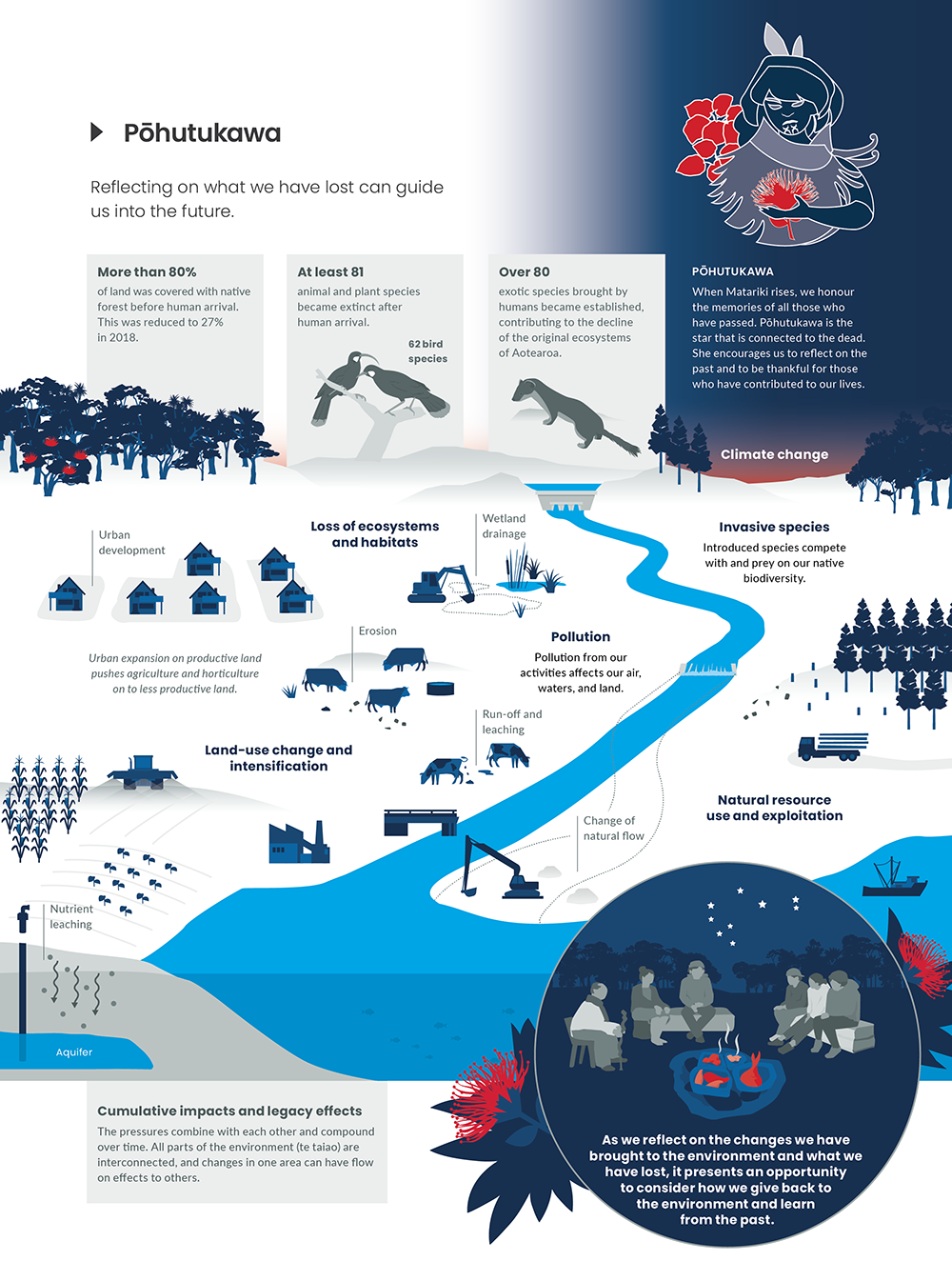

Pōhutukawa (Sterope/Asterope) is the eldest child of Matariki and is the star that is connected to the dead. When Matariki rises in the new year, Māori honour the memories of all the people who have passed, and their spirits are released to become stars. Pōhutukawa encourages us to reflect on the past and to be thankful for those who have contributed to our lives.

Pōhutukawa is connected to remembrance. A ceremony called ‘whāngai i te hautapu’ traditionally took place when Matariki had re-appeared in the mid-winter morning sky. The ceremony involved cooking and offering food to the different stars of Matariki, along with conducting karakia (incantations). Those who had died since the last rising of Matariki were honoured in the first part of the ceremony, when people would weep for their loved ones as their names were called out (Matamua, 2021).

For this report, Pōhutukawa represents the species and ecosystems we have lost and are at risk of losing, as well as the appreciation and duty of care we have for the environment (te taiao). When a species is gone its mauri extinguishes, and we are left with its memory and the lessons we can take from its departure (see the Matariki section for the definition of mauri used in this report). The loss of any part of the environment has a negative impact on our wellbeing when we recognise our connection to the environment. Furthermore, the loss is not just ours but a loss of opportunity and connection for future generations. Our gratefulness and duty of care is therefore to acknowledge the pressures we put on the environment and plan on how we can reduce them.

Image: Erica Sinclair, Erica Sinclair Photography

People’s impact on the environment is a result of complex socio-cultural, economic, and technological factors. These, ultimately, are embedded in systems of values – how we treat the environment we live in comes down to what we collectively view as most important. In broad terms, environmental value systems can be categorised as instrumental, intrinsic, or relational (Chan et al, 2020; Pascual et al, 2017).

Instrumental values represent the value of ecosystems to support human needs and goals (Pascual et al, 2017). In this case, nature is viewed as a resource to fulfil the needs of an individual or a society and provide utilitarian benefits, such as ecosystem services. Intrinsic values refer to the value of ecosystems by their own right. From this perspective we should value nature for its own existence, independent of any benefits it may provide us (Connor & Kenter, 2019).

By contrast, relational values are starting to be recognised as another system of values. They refer to a view that people and nature are inseparable. This perspective sees us as embedded within our environment, and often implies moral duties to care – as the environment supports us we have a reciprocal responsibility to take care of it (Chan et al, 2016).

The notion of relational value systems aligns most closely with Māori understandings of the environment, in which humans are connected to ecosystems and all living beings through whakapapa (genealogy). Whakapapa understands the total environment or whole system and its lineage, allowing us to see the ways we are connected to te taiao (Harmsworth & Awatere, 2013).

These different value systems exist together in a society, and understanding which value sets are used in decisionmaking and how this changes over time is still an active area of research (Hill et al, 2021). The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services gathered scientific evidence on the extent to which nature contributes to people in reciprocal ways and is vital for human existence. Their recent global assessment showed that by focusing on instrumental values, that is material supply of food, energy, and other tangible materials, human society has compromised many other contributions from nature (IPBES, 2019).

While the material benefits from the environment brought us economic gains, focusing entirely on instrumental values can result in loss of species and ecosystems, and the invisible or intangible benefits we receive from intact ecosystems. These include habitat for wildlife, flood and erosion control, and enhancement to our spiritual and psychological wellbeing (Powers et al, 2020; Tomscha et al, 2019).

Thinking differently about our relationship with the environment and recognising the full range of values can restore balance. To achieve this balance, we need to clarify how our actions are affecting the environment. The remainder of this section examines the pressures past generations have placed on te taiao, the legacy we are left with, and our own legacy for future generations.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, a diversity of values and cultural backgrounds have shaped and continue to shape the landscape as we see it today. Each generation has left a legacy that we can trace back to the first landing of humans. How the land gets used and transformed is informed by values such as the ones outlined above (Journeaux et al, 2017). Farming first by Māori, then early European settlers, became the most significant human influence and soon became the backbone of economy of Aotearoa (Haggerty & Campbell, nd).

Before human arrival, more than 80 percent of the land was covered with native forest. (See indicator: Predicted pre-human vegetation.) This reduced to 27 percent by 2018. Recently, indigenous land cover area losses have continued. Between 2012 and 2018, indigenous land cover area decreased by 12,869 hectares, with Southland having the highest area net loss (3,944 hectares) (See indicator: Indigenous land cover and Tupuārangi section).

Humans also brought with them exotic species, either inadvertently or intentionally. Over 80 exotic species brought by humans became established, further contributing to the decline of original ecosystems in Aotearoa (Craig et al, 2000). Due to its geographic isolation, Aotearoa has a high number of endemic species (found nowhere else in the world). The changes brought by human settlement resulted in the extinction of at least 81 animal and plant species, including 62 bird species (DOC, nd-b; Robertson et al, 2021). These changes are continuing.

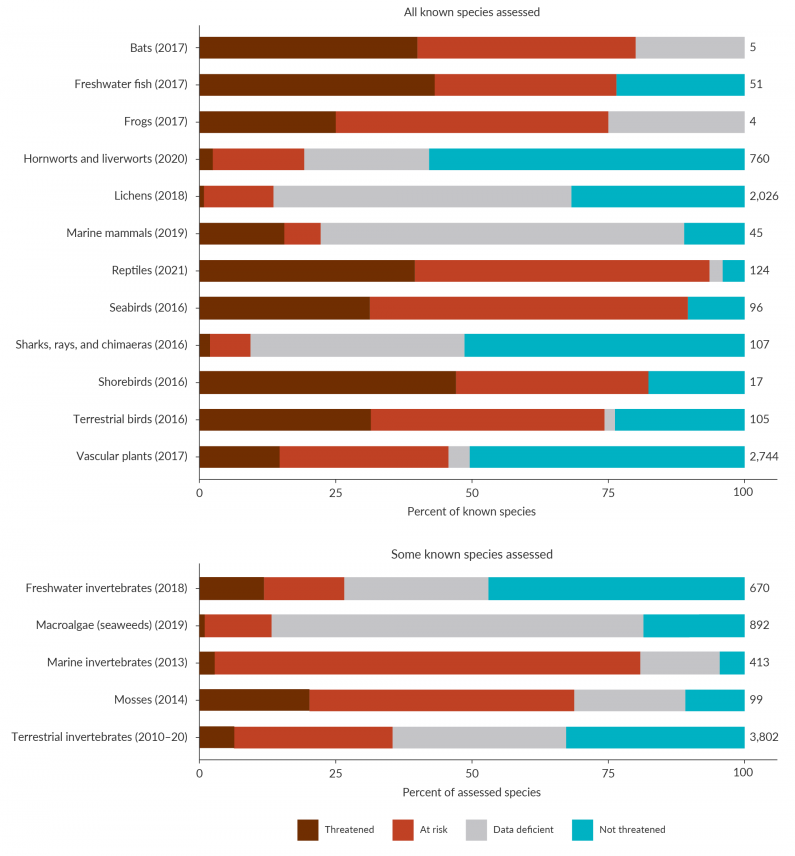

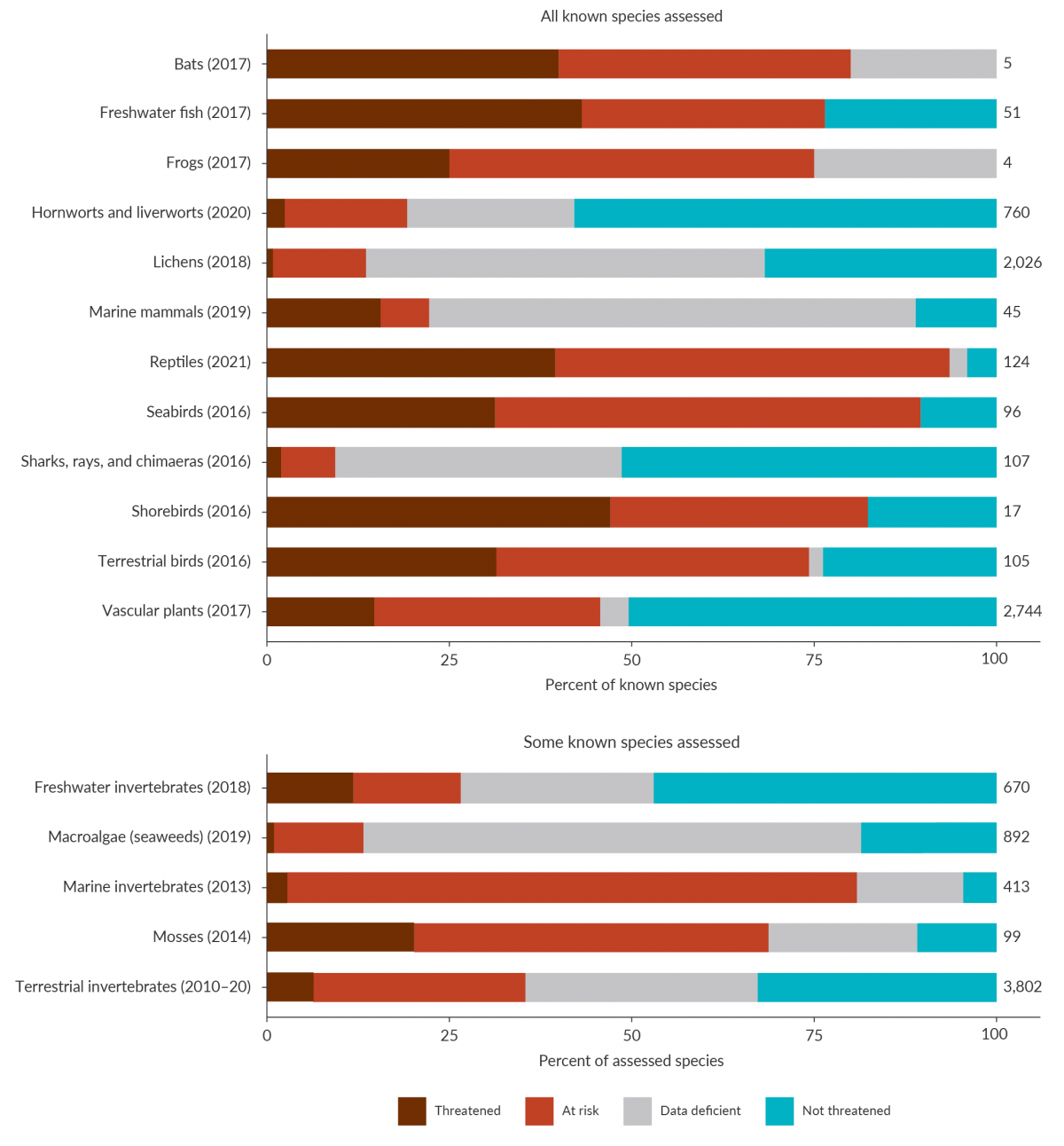

Figure 1 provides a summary of the state of our threatened land, marine, and freshwater species. Note that some groups have not had their extinction threat risk assessed for all species, so a comprehensive percentage of species in each extinction threat category is not available. (See indicators: Extinction threat to indigenous land species, Extinction threat to indigenous marine species, Extinction threat to indigenous freshwater species.)

Image: Data source — Department of Conservation

Image: Data source — Department of Conservation

He hokinga whakamuri he kokiringa whakamua

I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past

Drawing from previous reports in the environmental reporting series, this section synthesises the legacy of our past actions to understand what we leave for the future. The section reflects the broad themes we used in Environment Aotearoa 2019, and the five drivers of change known to have the biggest impacts on nature (land-use change, invasive species, pollution, natural resource use, and climate change) (IPBES, 2019). See the previous reports for a more comprehensive summary of pressures in each of the five environmental domains of our reporting system (marine environment, freshwater, atmosphere and climate, land, and air).

We have intensified our use of agricultural land in recent years, particularly through dairy farming and horticulture. Intensification involves increasing the use of inputs such as fertiliser and irrigation, with the aim of increasing production – for example, having more animals per hectare of land or increasing the number or volume of harvests from crops (MfE & Stats NZ, 2021a).

Much of the intensification has been a result of a switch from sheep to dairy farming, driven by higher relative global market prices for dairy products (Wynyard, 2016). Overall, dairy cattle numbers increased by 21 percent between 2002 and 2019. (See indicator: Livestock numbers.) In Aotearoa, dairying accounted for around 40 percent of export revenue for primary industries in 2021, which is expected to reach $50.8 billion for the year ended June 2022 (MPI, 2021f).

The area of exotic forestry in 2018 was 12 percent higher (220,922 hectares higher) than in 1996. Of the land area that changed to exotic forestry, three quarters was from the conversion of land that was previously exotic grassland. (See indicator: Exotic land cover.)

The area of irrigated agricultural land almost doubled between 2002 and 2017 from 384,000 hectares to 747,000 hectares – a 94 percent increase in this period. Between 2017 and 2019, the area of irrigated land fell 11,666 hectares, a 1.6 percent decrease compared to 2017. (See indicator: Irrigated land.) Also, as of 2018, about 10 percent of Aotearoa land was estimated to be artificially drained (see Our freshwater 2020).

The increase in fertiliser and irrigation use can deplete the health of our soils and pollute rivers and lakes. Clear felling of plantation forests, the harvest method used in Aotearoa, disturbs soils and increases sediment in waterways (MfE & Stats NZ, 2020b). These impacts and their implications for our wellbeing are discussed in the Tupuānuku section. See Our land 2021 for more detail on land-use intensification.

Intensification is also being driven by urbanisation and land fragmentation. Often highly productive agricultural and horticultural land, land that is particularly good for food production, is on urban fringes. As urban areas expand, this land is fragmented by housing development. The area of highly productive land that was unavailable for agriculture (because it had a house on it) increased 54 percent between 2002 and 2019. (See indicator: Land fragmentation.) This pushes agriculture and horticulture on to less productive land, which means farmers use more fertiliser and irrigation to maintain productivity (MfE & Stats NZ, 2021a).

The area of urban land in Aotearoa increased by 15 percent from 1996 to 2018. (See indicator: Urban land cover.) Urbanisation can reduce access to green and open spaces. See Tupuārangi section for more on access to and benefits from greenspace.

Land-use change and intensification is putting pressure on the unique ecosystems and native species of Aotearoa. Change in land cover is driving fragmentation of habitats and allowing invasive species to spread, a process being exacerbated by climate change (Macinnis-Ng et al, 2021).

Wetlands are one example of a rare ecosystem with high biological, cultural, and disaster resilience values that are under threat. It is estimated that 90 percent of wetlands have been lost since pre-human settlement (Dymond et al, 2021) due to draining, ploughing, or burning, with approximately 60 percent of remaining wetlands in a moderately to severely degraded state (Ausseil et al, 2011). See Waitī section for more on recent changes to wetland extent.

The threat from introduced plants and animals is one of the greatest pressures our native species and ecosystems are facing. Aotearoa has the second-highest recorded number of invasive species in the world, excluding overseas territories (Turbelin et al, 2017). Introduced land mammals such as stoats, possums, and rats are responsible for most of an estimated 26.6 million egg and chick losses for native bird species every year (Russell et al, 2015). The pressures these invasives put on populations of treasured (taonga) species impact on customary practices for Māori (see Tupuārangi section for impacts on tikanga (customs/protocols) and Māori knowledge (mātauranga Māori)). The pressures from invasive species also have an economic effect, particularly on agriculture. (See indicator: Land pests.)

Invasive weeds are similarly a major threat, often outcompeting native species (MfE & Stats NZ, 2021a). While control efforts have been underway for decades, we still lack comprehensive information about invasive weed distribution and rate of spread (PCE, 2021a). See Tupuānuku and Tupuārangi sections for how ecosystems are being affected by plant and animal land pests.

The aquatic ecosystems of Aotearoa are as unique as those on land, and pests in both the freshwater and marine environments pose a major threat. Introduced fish, invertebrate, and plant species reduce native biodiversity and lower water quality. Between 2015 and 2017, three additional non-native marine species were considered to be established in the waters of Aotearoa, bringing the total of non-native marine species that are established to 214 (MfE & Stats NZ, 2019). The impacts of pest species are compounded by climate change – for instance, marine heatwaves can reduce the population of native species in an area, potentially enhancing the likelihood that empty spaces are re-colonised by non-natives (MfE & Stats NZ, 2019; Thomsen et al, 2019). (See indicators: Freshwater pests, Marine non-indigenous species.)

Our waterways are particularly vulnerable to pollution in various forms, as waste from the land is washed, pumped, or leached into the rivers and then to the sea. Plastic waste is a major problem: plastic takes centuries to break down, and large quantities continue to be produced. For example, in 2018 Aotearoa imported 575,000 tonnes of plastic material (PMCSA, 2019). A significant proportion of this accumulates in the environment, and plastics are found in the most remote areas and in the bodies of many animals. There is much we still do not know about quantities of plastics in the environment and the extent to which they affect ecosystems (MfE & Stats NZ, 2019; PMCSA, 2021). See Waitā section for what we are learning about how plastics impact the marine environment.

Land-use change and intensification increases pollution in our waterways. The amount of pollutants entering streams, rivers, and the ocean is linked to intensified agriculture and forestry, drained wetlands, industry, and urban development (McDowell et al, 2021; MfE & Stats NZ, 2020b). The environmental impacts we are seeing today are in many cases the result of decisions made in the past. For instance, fertilisation of agricultural land and urine from livestock impacts soil health and leaches nitrogen into waterways. However, water does not always move quickly through a catchment, and there are lag times between when the fertiliser was applied to the land and when the effects are evident in ecosystems. For a selection of river systems, the median lag time was estimated to be around five years, while in some catchments it can be many decades before the water completes its journey (McDowell et al, 2021; MfE & Stats NZ, 2020b). This has downstream effects on rivers, lakes, estuaries, and marine environments. Sediment accumulation has been identified as one of the main pressures on estuaries (see Our marine environment 2019).

Air pollution from vehicles, wood burning, and manufacturing comes at a cost to human and environmental health. Despite having sites that register pollution levels above World Health Organization 2021 guidelines, especially during winter months, air quality in Aotearoa is slowly improving at monitored sites. This demonstrates that environmental pressures can be reduced through concerted effort (MfE & Stats NZ, 2021b). See Ururangi section for levels of air pollution and their effects.

Prioritising the productive capacity of the environment runs the risk of over-exploitation of many natural resources beyond the capacity of the environment to sustain us over the long term. Modelling shows that the quantity of water taken for irrigation had the most potential to affect and reduce river flows compared to other uses (Booker & Henderson, 2019). Furthermore, global warming has reduced the volume of ice in our glaciers and the water available for the rivers they feed. (See Waipunarangi section and the Annual glacier ice volumes indicator.)

Structures for diverting or controlling water such as dams, weirs, fords, and floodgates also put pressure on ecosystems. Blocking waterways and altering flow patterns alters the natural integrity of rivers and their ability to adjust, impacting their mauri. These barriers and changing water flows affect the migration and spawning of taonga species such as whitebait (īnanga) (MfE & Stats NZ, 2020b). See Waitī section for more on these impacts.

In the marine environment, some fish species are overfished, and seabed trawling and dredging, although decreasing, can still damage habitat and alter the structure of the seabed (see Our marine environment 2019). The Waitā section reports on the state of key fish stocks, the majority of which are considered to be fished within safe limits. The pressures which result from overfishing are still reducing the availability of important seafood (kai moana) species, and the tikanga and mātauranga Māori associated with collecting them. Many of these species face further stress from other pressures such as ocean acidification from carbon emissions.

Our climate is changing, and this will continue to increase pressures on all parts of the environment (see Our atmosphere and climate 2020). Greenhouse gas emissions have increased globally, and the concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere continues to rise (Ritchie & Roser, 2020).

Aotearoa is also contributing to this issue. In 2020 Aotearoa’s gross greenhouse gas emissions (or total emissions) were 21 percent higher than 1990 levels but have been relatively stable over the last decade despite increases in population and economic activity. For the same year, the country’s net emissions (total emissions plus any emissions added or removed by the land use, land-use change and forestry sector) were 26 percent higher than 1990 levels (MfE, 2022). As long as our net emissions are greater than zero, we are still contributing to further climate change (MfE & Stats NZ, 2020a). In 2020, agriculture accounted for 50 percent of our total gross emissions, mainly from livestock (39 percent of gross emissions; 78 percent of the agriculture sector) and agricultural soils (10 percent of gross emissions; 20 percent of the agriculture sector). This was followed by energy at 40 percent, with energy for transport accounting for 17 percent of gross emissions; 42 percent of the energy sector (MfE, 2022).

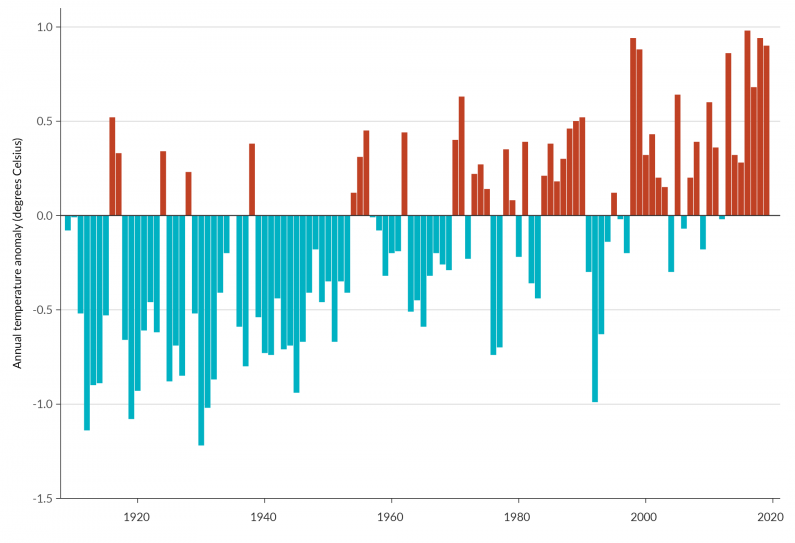

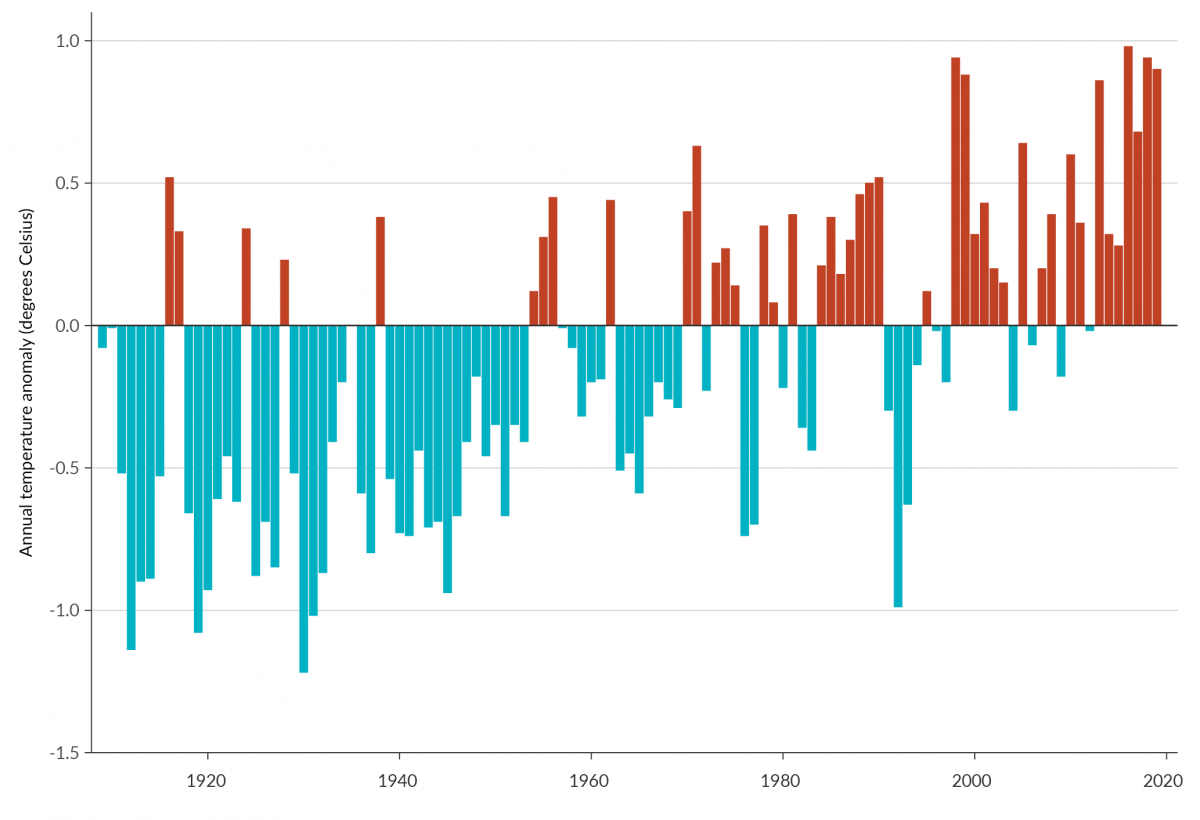

The greenhouse gases we and the rest of the world emit are creating a warming effect in the climate. Overall, average temperatures are increasing (see figure 2). In Aotearoa, the annual average temperature increased by 1.13 (± 0.27) degrees Celsius over the period 1909 to 2019. In the 22 years to 2019, Aotearoa had its five warmest years on record: in 1998, 1999, 2016, 2018, and 2019. In the period from 1972 to 2019, 28 out of 30 monitored sites showed an increase in annual average temperature (the increasing trend was statistically very likely at 25 sites and likely at 3). (See indicator: Temperature.) The annual cumulative amount of warmth available has likely or very likely also increased at 27 of the 30 monitoring sites over the same period. (See indicator: Growing degree days.) For trend assessment detail, see relevant indicators.

Image: Data source — NIWA

Image: Data source — NIWA

A warming atmosphere also impacts weather patterns, including precipitation, seasonal temperature (frost and warm days), and wind patterns. The Waipunarangi and Ururangi sections cover the observed changes in climate and impacts of flooding and drought (Waipunarangi) and wind (Ururangi) on our wellbeing. The Tupuārangi, Waitī and Waitā sections cover the effects of changes in climate on some species in the land, freshwater, and marine domains.

The way we view nature, and the subsequent choices in the ways we live and make a living, result in pressures on the environment. These pressures can result in the loss of ecosystems and species, negatively impacting different aspects of our wellbeing. We explore the connections between environmental pressures and our wellbeing in the coming sections.

Many of these pressures will continue to have an impact, leaving a legacy effect on the wellbeing of future generations. Our duty of care is therefore to acknowledge the pressures we put on the environment and plan on how we can reduce them.

Pōhutukawa: When Matariki rises, we honour the memories of all those who have passed. Pōhutukawa is the star that is connected to the dead. She encourages us to reflect on the past and to be thankful for those who have contributed to our lives.

Reflecting on what we have lost can guide us into the future.

Cumulative impacts and legacy effects: The pressures combine with each other and compound over time. All parts of the environment (te taiao) are interconnected, and changes in one area can have flow on effects to others.

As we reflect on the changes we have brought to the environment and what we have lost, it presents an opportunity to consider how we give back to the environment and learn from the past.

Pōhutukawa: When Matariki rises, we honour the memories of all those who have passed. Pōhutukawa is the star that is connected to the dead. She encourages us to reflect on the past and to be thankful for those who have contributed to our lives.

Reflecting on what we have lost can guide us into the future.

Cumulative impacts and legacy effects: The pressures combine with each other and compound over time. All parts of the environment (te taiao) are interconnected, and changes in one area can have flow on effects to others.

As we reflect on the changes we have brought to the environment and what we have lost, it presents an opportunity to consider how we give back to the environment and learn from the past.

Pōhutukawa Loss, extinction, gratefulness to the environment (te taiao)

April 2022

© Ministry for the Environment