Clause 3.16: Setting environmental flows and levels

Environmental flows and levels are a measure of water quantity, expressed as water level and flow rates and flow variability. They apply to the whole FMU, which may include lakes, rivers, groundwater or a combination of them.

Councils must maintain flows and levels in a water body, to provide for its values and outcomes.

An environmental flow regime aims to retain enough volume, flow and level variability in the water body. It does this by limiting (a) the total amount of water that can be taken and (b) the taking of water when particular flows and levels are reached. The regime includes the take limits (clause 3.17) and minimum and other flows.

‘Water quantity – the extent and variability in the level or flow of water’ is one of five biophysical components for the ecosystem health value in appendix 1A – Compulsory values that apply to every FMU.

As outlined in clause 3.9 (‘Identifying values and setting environmental outcomes as objectives’), regional councils, with tangata whenua and the community, must identify the values and think about how the flows and levels will help achieve the outcomes.

Flows and levels are also important for achieving outcomes for other values such as mahinga kai, natural form and character, and recreational uses such as kayaking. Many values will in some way be influenced by flows and levels. Some freshwater attributes (eg, the Macroinvertebrate Community Index) are particularly sensitive to changes in flow and levels.

Below are examples of the importance of environmental flows and levels for many values.

Setting environmental flows and levels is not a new requirement for councils and many may have already set rules in their plans under the NPS-FM 2014. However, the NPS-FM 2020 contains more specific direction about how to set environmental flows and levels.

The main change is the strengthened concept of Te Mana o te Wai in the decision-making process and ensuring that decisions give effect to it. Councils must be confident that existing rules meet this fundamental concept and the hierarchy of obligations, and that the flows and levels are sufficient to maintain or improve the ecosystem health of the water body and connected water bodies.

Regional councils must set environmental flows and levels as rules in their regional plans. This must achieve both the outcomes for the values relating to all or part of the FMU, and all relevant long-term visions. This obligation recognises the importance of water quantity for the compulsory values of ecosystem health and mahinga kai, but also for social and cultural values (eg, recreational fishing). These values often go hand in hand, because a water body is unlikely to have high recreational and cultural values in the absence of a healthy ecosystem.

In the NPS-FM 2014, environmental flows and levels were defined as:

a type of limit which describes the amount of water in a freshwater management unit (except ponds and naturally ephemeral water bodies) which is required to meet freshwater objectives. Environmental flows for rivers and streams must include an allocation limit and a minimum flow (or other flow/s). Environmental levels for other freshwater management units must include an allocation limit and a minimum water level (or other level/s).

Take limits were considered as one type of limit, including minimum flows.

An important change to the above definition is that flows and levels are no longer considered a type of limit. In the NPS-FM 2020, they are now a more comparable measurable characteristic for water quantity, similar to how a TAS is a measurable characteristic for water quality.

The distinction between environmental flows and levels, and limits is important.

Flows and levels should now be clearly linked to achieving environmental outcomes, the long-term vision in the regional policy statement, and in line with Te Mana o te Wai.

The requirement to set flows and levels applies to rivers, lakes and groundwater. They must meet the outcomes of any connected water body or receiving environment, which will include wetlands, and, in some cases, water bodies connected to the coastal marine area (such as estuaries). Because the outcomes must be met for all, the most sensitive environment will determine how the flows and levels are set.

The direction for setting the flow regime is directly related to take limits (clause 3.17). Of particular importance, regional plans must:

Setting flows and levels, and take limits, is part of the NOF process for applying the NPS-FM. Subparts 1 and 2 apply equally to environmental flows and levels, as they do to setting TASs. This includes actively involving tangata whenua and engaging with communities at every stage of the process.

Like TASs, flows and levels are one way of achieving environmental outcomes and the long‑term visions.

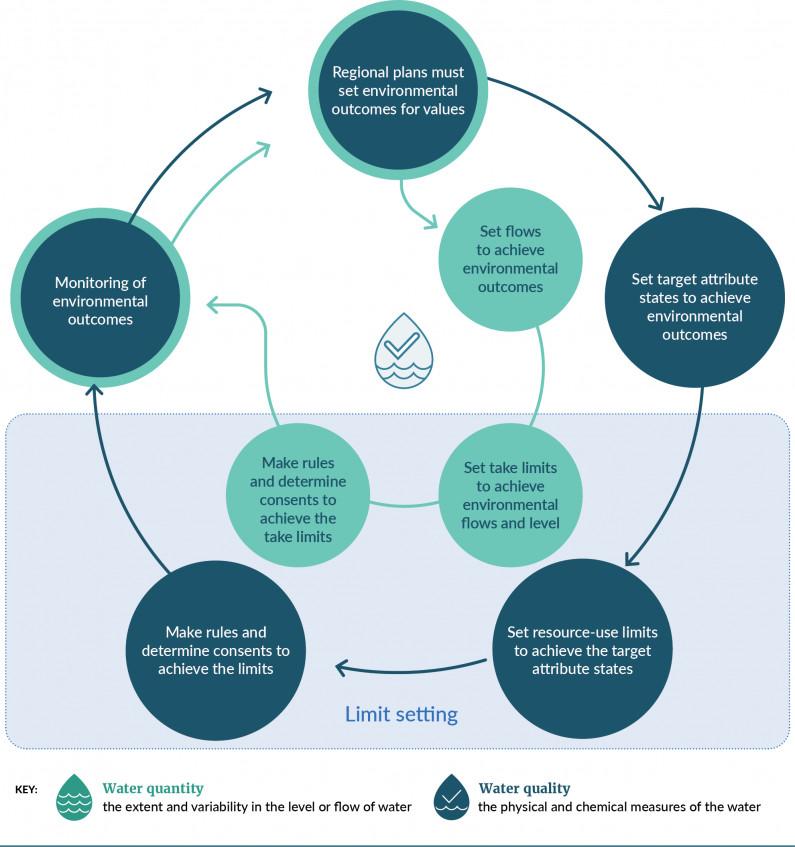

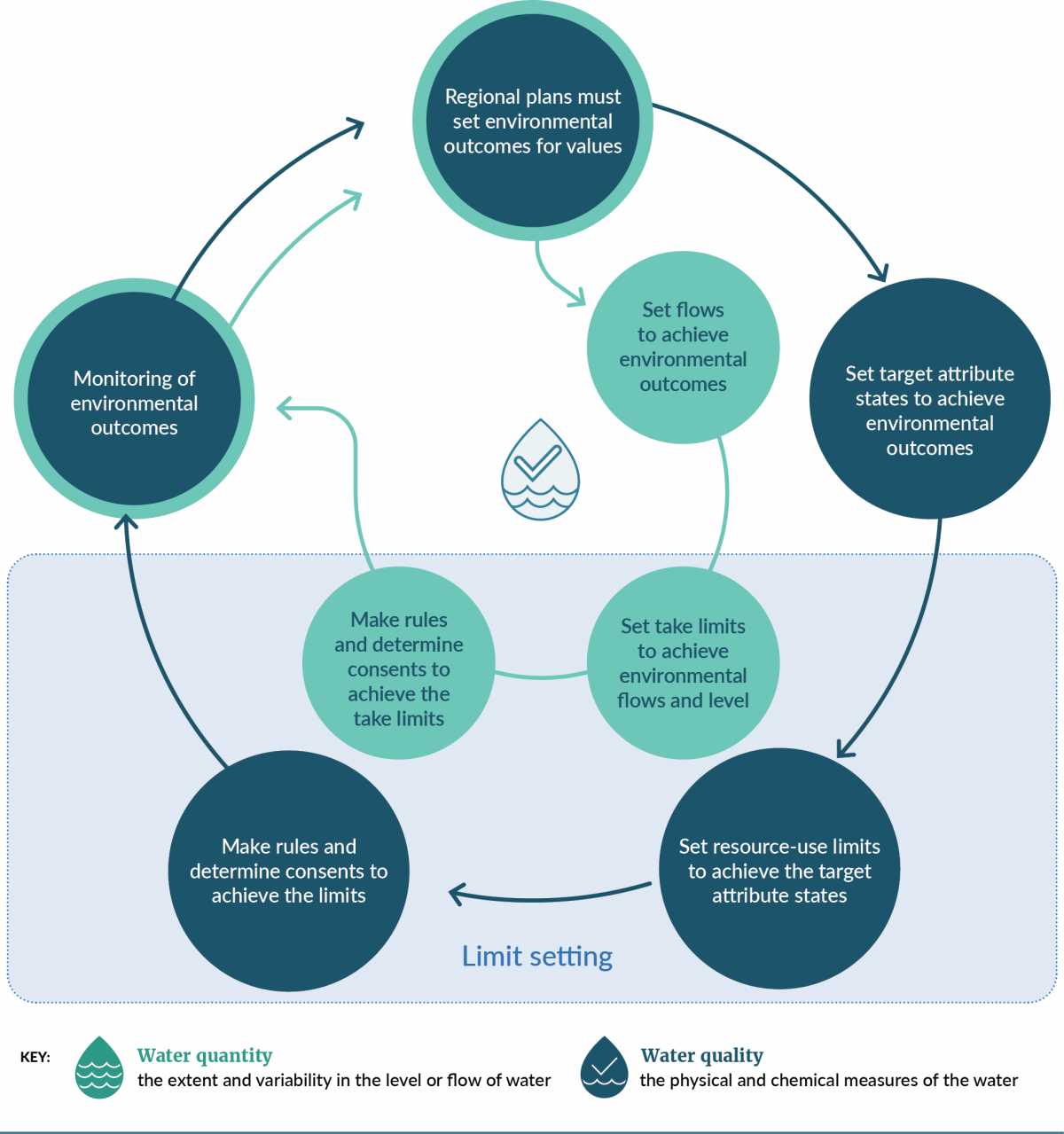

The processes for setting and achieving quantity and quality limits now align as shown figure 8.

This diagram illustrates the circular method of settling environmental limits for water quality and water quantity.

Water quantity is the extent and variation in the level or flow of water

Water quantity limit setting is achieved in this order:

Starts again at regional plans must set environmental outcomes for values.

Water quality is the physical and chemical measures of the water

Water quality limit setting is achieved in this order:

Circle starts again at: Regional plans must set environmental outcomes for values.

This diagram illustrates the circular method of settling environmental limits for water quality and water quantity.

Water quantity is the extent and variation in the level or flow of water

Water quantity limit setting is achieved in this order:

Starts again at regional plans must set environmental outcomes for values.

Water quality is the physical and chemical measures of the water

Water quality limit setting is achieved in this order:

Circle starts again at: Regional plans must set environmental outcomes for values.

Setting flows and levels requires a more holistic consideration of the ‘suite of flows’ (beyond minimum flows and allocation) to protect ecosystem health and other values. Under the NPS‑FM, a flow can be considered the quantity, variability, flow, duration and timing of flows or water levels to give effect to Te Mana o te Wai, the long-term visions and outcomes set by the community and tangata whenua.

The NPS-FM sets out policy direction clarifying that further decline in the health and well-being of water bodies is not acceptable. In many catchments and aquifers, current freshwater limits may not be sufficient to achieve the environmental outcomes. It may take time for existing water users to adjust to differences in water availability. Flows and levels can be set and adapted over time to take a phased approach to achieving environmental outcomes and long-term visions.

The NPS-FM also requires councils to consider the effects of climate change, and they may provide time to adapt and respond as more information becomes available and mitigation options change.

Councils are unlikely to have real data for every water body in their region due to the difficulty and expense of monitoring all. In this instance, councils will need to use modelled data and approximate methods to set environmental flows and levels. Further detail on using best available information is given below.

Councils must take a holistic approach (ki uta ki tai) to managing flows throughout the FMU. Decisions must recognise the interconnectedness of the whole environment. There will be a connection between flows and levels and achieving TASs; these must be developed in tandem.

The requirement to maintain or improve the health of water bodies and freshwater ecosystems applies at all times and across the FMU. This may involve gauging vulnerable tributaries and establishing relationships with low flows at downstream recorders.

The following are examples of interconnectedness:

A significant change in the NPS-FM 2020 is strengthening Te Mana o te Wai as the fundamental concept. This recognises that protecting the health of freshwater protects the health and well-being of the wider environment.

A requirement is also in place for tangata whenua involvement in the local definition and approaches to giving effect to Te Mana o te Wai, including use of mātauranga Māori and other attributes for values such as mahinga kai. These could result in changes to the decisions about setting environmental flows and levels, and take limits, and may require a change to existing rules.

Decisions to prioritise the health and well-being of the water body may be fraught with uncertainties about information. However, councils should take a precautionary approach and not delay decisions.

The eight steps below are a suggested best practice example for setting environmental flows and levels.

The way the steps are taken, and the result, will vary for different types of water body. For example, groundwater, spring-fed and braided water bodies will have different influencing factors (climate, topography and so on) that will affect the characteristics of the flow. The flow characteristics should link to the environmental outcomes.

Unlike the other four components of the ecosystem health value, the NPS-FM does not prescribe attributes for environmental flows. It prescribes the overall design framework, including details of how the regime must be expressed in plans, but leaves flexibility for councils to use their own methods for determining what their regime is, and how the flows and levels will be set.

Regional councils may find it useful to develop narrative attribute tables to support their flow and levels regime. Table 2 shows a sample narrative attribute table for water quantity.

|

Value |

Ecosystem health |

|---|---|

|

Water body |

Rivers |

|

Attribute |

Habitat as affected by human induced flow variations |

|

A |

Abundant, diverse habitat to support species assemblage and abundance expected without water abstraction or diversion. Sufficient natural flow variability to influence channel morphology and bed movement. The flow regime provides for all ecosystem processes. |

|

B |

Reduced habitat but of short duration. Effects of abstractions or diversions can be mitigated (eg, by shading or increasing flow). A variety of flows to influence substrate movement. The flow regime provides for all ecosystem processes. |

|

C |

Some reduced habitat of long duration, but still enough to support the species. Variety is reduced. |

|

D |

Inadequate abundance or diversity of habitat to provide for the diversity of native flora and fauna. Remaining habitat cannot sustain populations long term. Aquatic species are likely to be become stressed if flow stays at this level for an extended time. |

|

E |

Inadequate connectivity with other water bodies. Indigenous species are stressed by high temperatures and low dissolved oxygen in the water. Insufficient food and space for the species that have lived there. |

Source: Interim Regulatory Impact Analysis for Consultation: Essential Freshwater Part II: Detailed Analysis (Ministry for the Environment, 2019)

Councils may have already set their flows and levels, including existing minimum flows, in their regional plans. However, they must review these to ensure they give effect to Te Mana o te Wai.

Many minimum flow regimes were set to provide for the needs of trout or salmon, and some were set to provide for out-of-stream values, such as economic and social needs, ahead of maintaining instream values. The hierarchy in Te Mana o te Wai means the regime must first meet the health and well-being of water bodies and freshwater ecosystems. Providing for the needs of trout and salmon would be relevant where communities have identified ‘fishing’ as a value in the FMU.

In some cases, this may require a significant shift to maintain or improve the health of the water body (Policy 5 of the NPS-FM). Adjusting to this new framework may take time, especially in over-allocated catchments that may need significant change.

The council, tangata whenua and community will need to set timeframes for achieving flows and levels that align with the timeframes for the long-term vision. The regional plan should clearly set out the flow and level timeframes. As suggested with target attribute states and limits, a look-up table may be a useful way to transparently show the transition from an over-allocated state to flows and levels that achieve the long-term vision.

Councils may phase in the changes to water management. For example, plan rules can have X cubic metres per second (m3/s) environmental flow in 5 years and Y m3/s in 10 years, to show the progression towards the long-term vision. This will require consultation with the community, and applies to every water body in the catchment, not just the main river stems.

If a water body is currently a long way from achieving the environmental flows and levels that are needed to achieve the values, councils may need to phase in the reduced takes over a period of years. As noted above, section 68(7) of the RMA enables plans to specify a phased approach for existing consents.

When determining the time for adjustment, the following will be important matters for communities to consider:

The time allowed must meet the timeframe in the long-term vision.

Councils should provide clarity about when they will review resource consents and change the flow regimes so that investment decisions can be made about water infrastructure.

Environmental flows and levels must be set as rules in plans. They are the ‘cut-off’ or threshold rules, whereas take limits are the maximum amount that can be taken. For example:

When setting environmental flows and levels as rules in the regional plan, regional councils have the option to use section 68(7) of the RMA to specify a phased approach for existing consent holders over time. Once rules are in place, regional councils may also use section 128(1)(b) of the RMA to review existing resource consent conditions in light of the new environmental flows and levels.

Councils are unable to cancel existing consents unless the requirements in RMA section 128(1)(c) regarding inaccuracies in a consent application have been met, a consent review has been ordered as part of a penalty for an offence under the RMA, or the consent holder has requested cancellation. However, reviewing and adjusting consent conditions is an important tool for achieving new flow and level regimes over time. Councils can state in their plan(s) that, in catchments that are over-allocated, consents will be reviewed by a certain date. New consents would not be able to be granted in over-allocated catchments.

The flow and level rules for each FMU may vary from the typical ‘activity-based’ rules in regional plans. A rule more like that found in other regulations may be required. This type of framework is common in many water conservation orders.

If a minimum flow is part of the flow regime, this may require a rule that states ‘no water may be taken when the flow in x stream drops below x level’.

In some river systems with multiple water takes a suite of flows may be set according to clause 3.16, and a suite of take limits set according to clause 3.17. The take limits could be classed as A, B or C-type permits.

For example, where an A permit is for water supply, it can continue to operate until the flow falls to the lowest flow set under clause 3.16. If the flow falls below that threshold due to natural processes, no further water may be taken until the flow returns above the environmental flow framework in appendix x.

For a less complicated catchment with fewer take pressures, it may be enough to restrict the percentage of the instantaneous flow that may be taken at any time.

Suggested approaches for setting environmental flows and levels are as follows.

Climate change is expected to exacerbate the pressure on environmental flows by affecting when, where and how much rainfall, snowfall and drought occur. This in turn will affect the quantity of water in rivers and groundwater.

Higher temperatures increase evaporation and the demand for freshwater, including for irrigation. Climate change may also cause more frequent, heavy and intense rainfall, affecting ecosystem health such as sensitive aquatic life, but also providing benefits by flushing contaminants. Increasing water temperatures could be an additional stressor.

These are all factors to consider when setting flows, levels and take limits. After providing for the health and well-being of water bodies, consider how to efficiently allocate water, within limits, due to lower (or higher) capacity to provide for people’s health and social, economic and cultural well-being. In areas where climate change is likely to cause more frequent droughts (such as Hawke’s Bay and Northland), permit holders may need to prepare for more frequent suspension of their water take by harvesting water at higher flows and storing in off-line dams.

When setting environmental flows and levels, every council must use the best information available at the time. If there is not enough data on flows for all small streams (or other water bodies) in a catchment, a council could rely on modelled information. This default approach should reflect the principles of Te Mana o te Wai and be cautious about the streams and instream values.

Councils should set a level they are confident will protect the values, until there is more detailed information. More information can then be required as part of any application to take water from the stream, and can demonstrate that reduced flows will not compromise the values.

There are many uncertainties with natural flow variability, and limited data and knowledge. When making management decisions, councils should consider the following but note the best information obligation to keep making decisions.

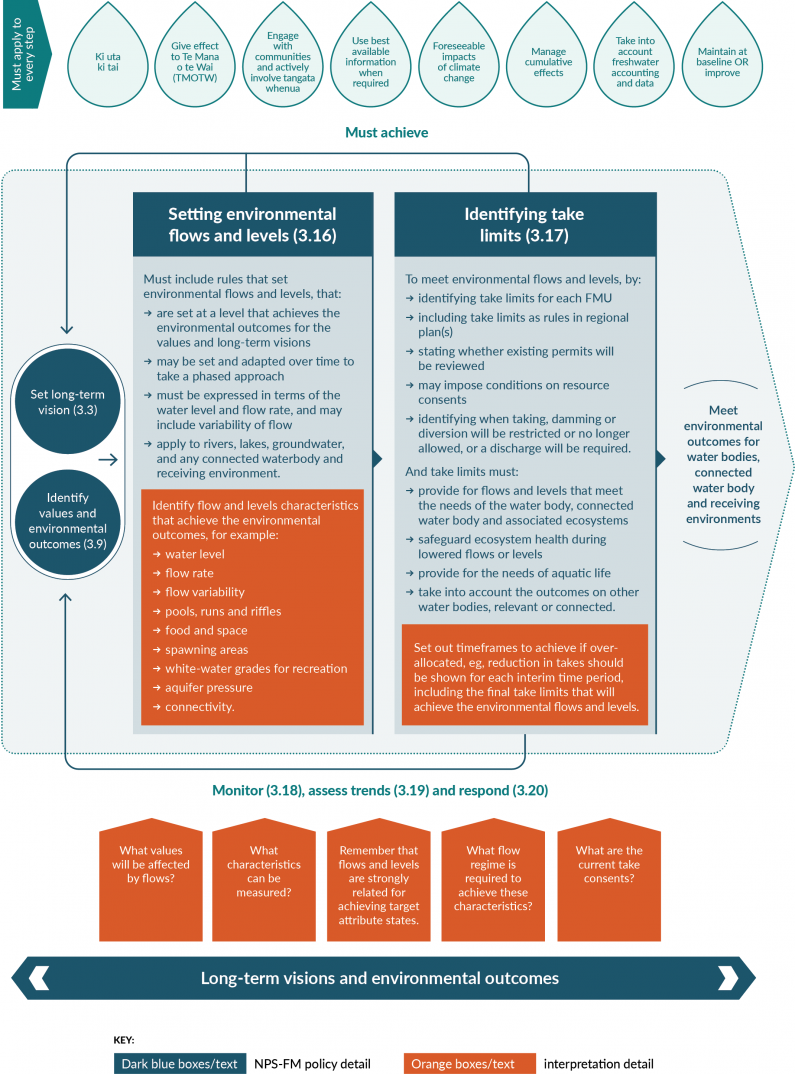

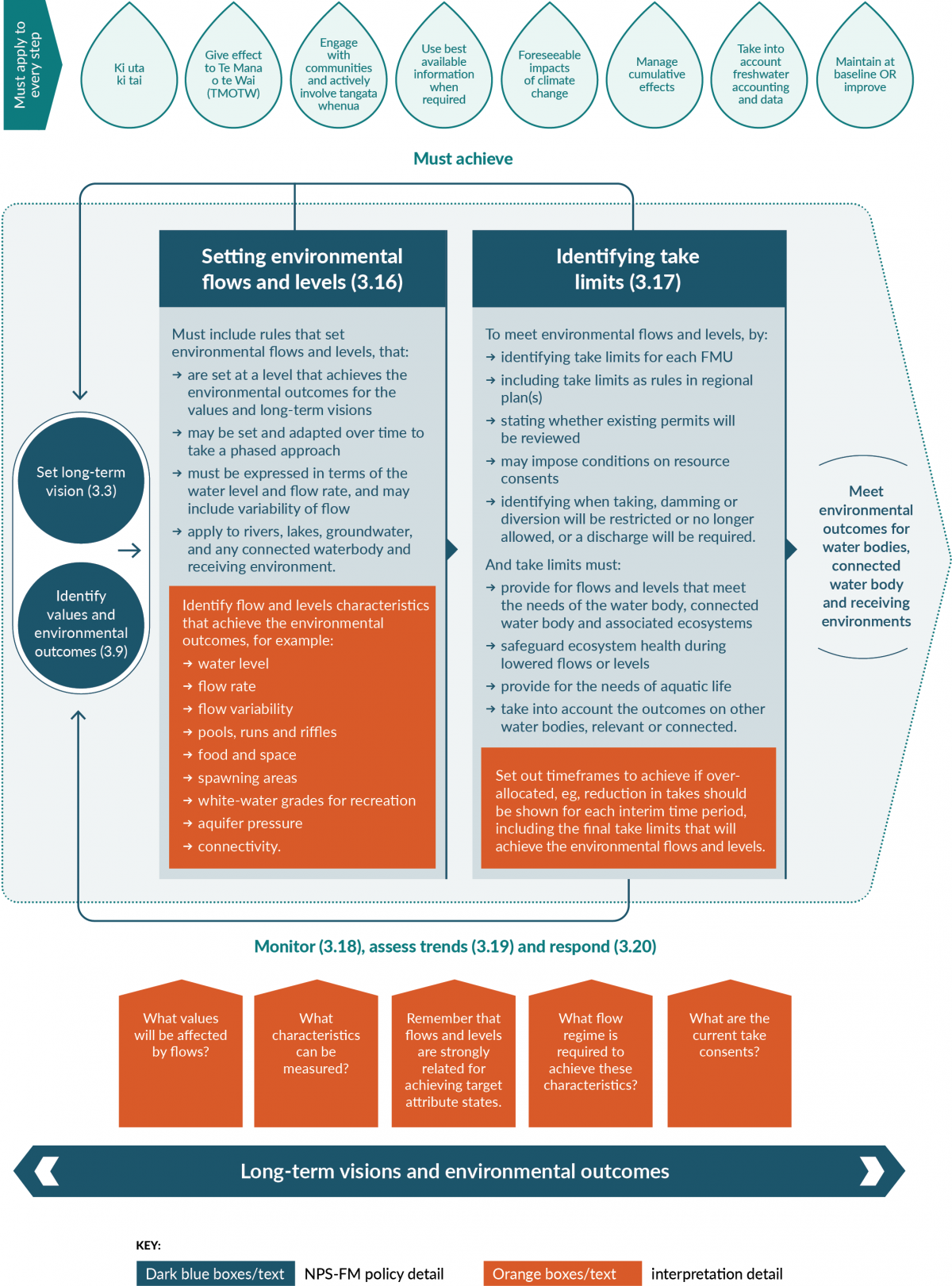

Figure 9 sets out the process for setting flows and levels, and identifying take limits as described in the next section.

Along top:

Matters that must apply to every step of the process

Multi-directional diagram on long-term visions and environmental outcomes to meet outcomes for water bodies, connected water body and receiving environment that shows relationship between:

Long-term vision and environmental outcomes are achieved when all relevant and described clauses are also achieved.

Setting environmental flows and levels (section 3.16)

To set rules to protect environmental flows and levels characteristics that:

A connecting arrow from this clause shows that setting environmental flows and levels must achieve the long-term vision for freshwater.

A directional arrow shows that 3.17 is the next step after 3.16.

Interpretation detail added to diagram:

Identify flow and level characteristics that achieve the environmental outcomes, for example:

Identify take limits (3.17)

To meet environmental flows and levels, by:

And take limits must:

An arrow shows that this clause should lead to meeting environmental outcomes for waterbodies, connected waterbody and receiving environments.

Interpretation detail note:

Set out timeframes to achieve if over-allocated, eg, reduction in takes should be shown for each interim time period, including the final take limits that will achieve the environmental flows and levels.

A connecting arrow labelled Monitor (3.18), assess trend (3.19) and respond (3.20), starts at Identifying take limits (3.17) and loops back to Setting longterm visions (3.3) and Identifying values and environmental outcomes (3.9), illustrating how progress is evaluated.

Interpretation questions and notes add detail when identifying long-term visions and environmental outcomes:

Along top:

Matters that must apply to every step of the process

Multi-directional diagram on long-term visions and environmental outcomes to meet outcomes for water bodies, connected water body and receiving environment that shows relationship between:

Long-term vision and environmental outcomes are achieved when all relevant and described clauses are also achieved.

Setting environmental flows and levels (section 3.16)

To set rules to protect environmental flows and levels characteristics that:

A connecting arrow from this clause shows that setting environmental flows and levels must achieve the long-term vision for freshwater.

A directional arrow shows that 3.17 is the next step after 3.16.

Interpretation detail added to diagram:

Identify flow and level characteristics that achieve the environmental outcomes, for example:

Identify take limits (3.17)

To meet environmental flows and levels, by:

And take limits must:

An arrow shows that this clause should lead to meeting environmental outcomes for waterbodies, connected waterbody and receiving environments.

Interpretation detail note:

Set out timeframes to achieve if over-allocated, eg, reduction in takes should be shown for each interim time period, including the final take limits that will achieve the environmental flows and levels.

A connecting arrow labelled Monitor (3.18), assess trend (3.19) and respond (3.20), starts at Identifying take limits (3.17) and loops back to Setting longterm visions (3.3) and Identifying values and environmental outcomes (3.9), illustrating how progress is evaluated.

Interpretation questions and notes add detail when identifying long-term visions and environmental outcomes:

Clause 3.16: Setting environmental flows and levels

July 2022

© Ministry for the Environment