Clause 3.18: Monitoring

Councils must establish methods for monitoring progress towards achieving TASs and environmental outcomes. The aim is to create a regular feedback loop.

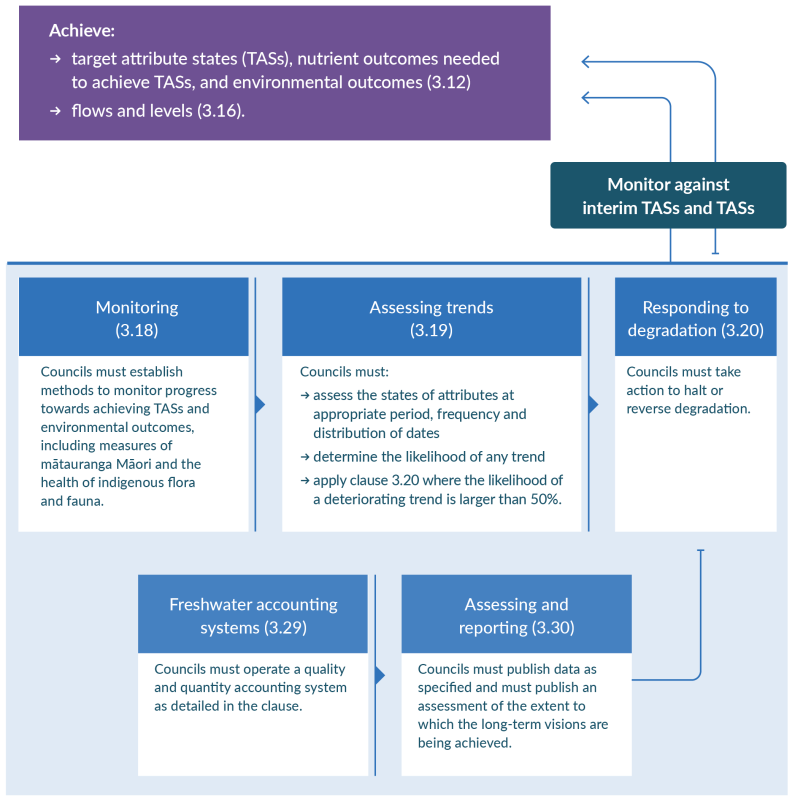

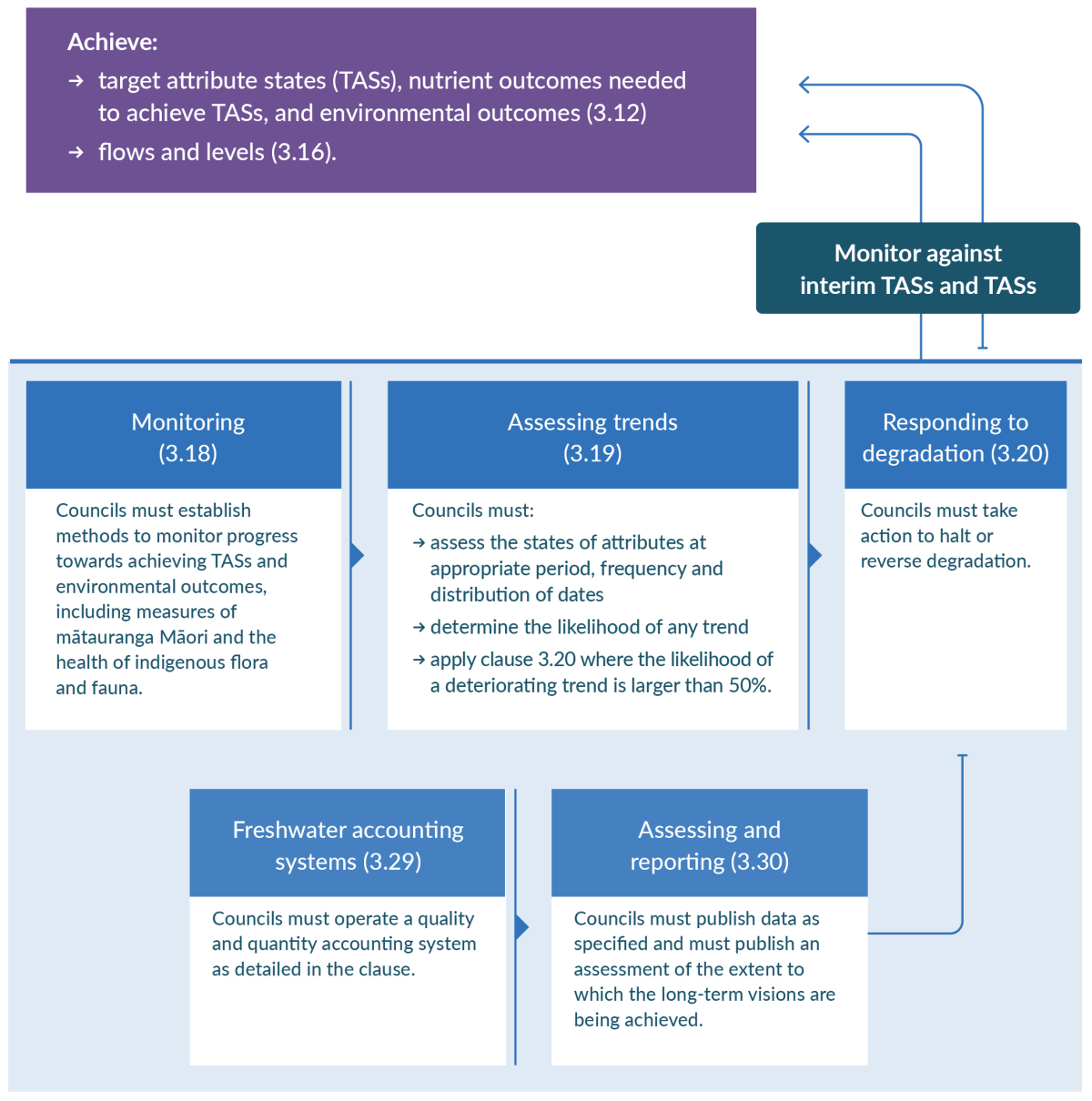

The loop allows councils to act in a timely manner if monitoring shows the outcomes as expected. It shows whether the limits, consent conditions, action plans and other methods are achieving the outcomes and interim goals, and are keeping the FMUs on track to achieve the long-term vision on time. Figure 11 provides a visual representation of this feedback loop.

Each attribute will be monitored at a representative site in the FMU or catchment. The attribute will be assigned a TAS at that monitoring site. The purpose of setting TASs for each monitoring site is so councils can continue to monitor progress at that specific site, and keep track of whether the intervention (eg, limit as a rule in regional plans and action plans) is having an effect and achieving the TAS over time. For efficiency and practicality, it is intended that (where appropriate), councils will monitor more than one attribute at any given monitoring site.

Infographic identifying the two pathways in freshwater management of the policies that must be implemented to achieve target attribute states (TASs), nutrient outcomes needed to achieve TASs, and environmental outcomes (3.12), and flows and levels (3.16).

Pathway 1

Pathway 2

Infographic identifying the two pathways in freshwater management of the policies that must be implemented to achieve target attribute states (TASs), nutrient outcomes needed to achieve TASs, and environmental outcomes (3.12), and flows and levels (3.16).

Pathway 1

Pathway 2

The NPS-FM does not prescribe specific methods of monitoring, or directions for a monitoring programme. However, the monitoring method must be fit for purpose. It must be a bona fide attempt to assess whether the TASs are being reached and the outcomes are being achieved.

These provisions are linked to other monitoring and reporting requirements in the NPS-FM, including:

Well-designed monitoring will yield feedback for planning and allow quick changes to address any variation from the pathway to the long-term vision.

Efficient monitoring aims to assess a number of the NPS-FM requirements comprehensively. This will require careful design and site selection.

Aspects to consider include:

Bear in mind the locations of the target states when choosing monitoring sites. This is not to say you need to monitor each location. Downstream monitoring can sometimes account for what is happening upstream. It can be more efficient to monitor the sites that either will provide the most information on what is happening in the freshwater ecosystem in the FMU (eg, do not only monitor at the top of a river), or that will review the state of the most vulnerable or at-risk sites, such as receiving estuaries.

Where there is more than one monitoring site for the same attribute in an FMU, how do councils set limits and actions plans appropriately?

The intervention (rules/action plan) should be targeted at the most stringent TAS in the FMU, noting that the benefit of an action plan is to tailor at a finer scale than rules generally provide for. A decreasing trend at a particular monitoring site means your intervention is not effective and firmer action is required in the form of action plans, consent conditions, or adjustments to rules.

Councils are required to work with tangata whenua to develop monitoring methods in a way that is informed by mātauranga Māori. Mātauranga Māori encompasses traditional knowledge, and the transfer of knowledge, about the nature of the world. As a method, mātauranga Māori can articulate the state of our environment from a Māori perspective.

The practice of mātauranga Māori can be specific to each rohe, iwi or hapū, and while some tangata whenua groups may be happy to work with councils to draw on mātauranga Māori in monitoring, others may not. Therefore, in identifying existing methods, or developing new monitoring methods informed by mātauranga Māori, councils will need to work closely with their local iwi and hapū to develop a plan.

There will be no one-size-fits-all approach. Mātauranga Māori may underpin the attribute and TAS, and the method and approach to monitoring. Methods that are practical and are effective for monitoring attributes will more likely lead to successfully meeting outcomes and visions for a catchment or FMU. This is because the NOF is a cascade, and the monitoring data collected will directly influence how regional councils set environmental flows, issue consents, set limits and put in place action plans.

There are existing kaupapa Māori tools and frameworks, which tangata whenua may consider when working with councils to establish monitoring methods . Alternatively, tangata whenua may develop their own frameworks for their specific context. In many cases, these tools can be used to bridge between the gap between non-Indigenous science and mātauranga Māori and a te ao Māori worldview.

Monitoring should not be limited to the state of the water body. State-of-the-water monitoring is important, but any changes in state cannot be checked against trends in land use without also carefully monitoring both resource use and intensity (eg, stocking units). This is particularly important where there are lags that cause delayed response in water quality changes. Land use change data is often not collected regularly, but should be, as it forms an important part of the monitoring package. Without it, it is often hard to assess whether rules on resource use and land use are being implemented effectively.

Councils should also monitor on-farm data showing how limits are met and monitor this information against the changes expected in broader land use trends (eg, if the rules and actions aim to halt expansion or intensity, these should be measured).

Reporting of all monitoring data should support the freshwater stewardship roles of tangata whenua, the council and the Ministry, and allow good oversight. Interested parties may need access to information that underpins the regulatory provisions as set out in clause 3.29(4). This also includes annual monitoring data for attributes and other requirements as set out in clause 3.30. It should also include other regulatory data related to tracking cumulative effects of activities, eg, land use trends, so they can be transparently reported (clause 3.29) together with the ecosystem score card requirements in clause 3.30(4).

Clause 3.18: Monitoring

July 2022

© Ministry for the Environment